|

Part 1--Wheeler Amphitheater

Millard County in western Utah is world-famous for its

early Paleozoic fossil localities--a vast, sparsely inhabited

area that holds numerous prolific paleontologic places of middle

Cambrian through early Ordovician geologic age some 510 to 470

million years old. Indeed, this eastern Great Basin Desert region

could well hold the best preserved and most complete succession

of 510 to 485 million year-old middle to late Cambrian trilobites

in the world. The renowned Wheeler Amphitheater locality in particular--also

called Antelope Spring--in the House Range attracts eager paleontology

enthusiasts year-round to an extraordinarily productive commercial

fossil quarrying operation, where for a reasonable fee visitors

may collect common, complete trilobites from the middle Cambrian

Wheeler Shale, around 505 million years old; these include prodigious

numbers of stunning specimens of a genus-species scientists call

Elrathia kingii, probably the single most readily recognizable

trilobite variety on earth. It is indeed a world-class fossil

district.

While Cambrian trilobites continue to draw fossil seekers

to these breathtakingly beautiful Great Basin environs, there

are numerous additional sensational paleontologic localities

scattered across Millard County.

Probably the best of the lot is Fossil Mountain in the

informally designated Ibex District. Here can be found a veritable

treasure trove of wonderfully preserved invertebrate fossils

dating from the early Ordovician age of approximately 485 to

470 million years ago. Among the fossil groups documented from

Ibex are algae, brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, cephalopods,

conodonts, echinoderms, gastropods, graptolites, ostracods, pelecypods,

sponges, and trilobites. Preservation of the brachiopods in particular

rivals that of the Midwest region of the United States--specimens

universally regarded as the most exquisitely preserved late Paleozoic

(Mississippian, Pennsylvanian, and Permian Periods) organisms

in the world. Around 3,500 feet of lower Ordovician sedimentary

rocks are exposed at Ibex, and the material is for the most part

unmetamorphosed by the geologic forces of heat, pressure, and

hydrothermal alteration--pervasive processes that have invariably

obliterated much ancient animal life in Paleozoic Era strata

exposed throughout the western United States.

An excellent place to begin a Millard County paleontology

adventure is of course Wheeler Amphitheater in the House Range,

or as many fossil aficionados prefer to call the rich region:

Antelope Spring. That's where the fabulous middle Cambrian Wheeler

Shale attains its ultimate geological and paleontological development,

where quite conveniently that successful commercial fossil dig

allows visitors to come on in and collect for a reasonable fee

any number of whole, perfect trilobite carapaces.

The history of fossil collecting at Wheeler Amphitheater

probably begins with the prehistoric Ute Indians, who archaeologists

aver used not a few of the extinct arthropod trilobites as amulets

to help repel injury during battle. But there is no doubt that

a Henry Engelmann, who accompanied geologist J. H. Simpson on

the very first earth science expedition to Millard County in

the mid 19th Century, made the initial historic recorded trilobite

find at Antelope Spring in 1859. Simpson eventually provided

paleontologist/geologist Fielding Bradford Meek with the Wheeler

Amphitheater trilobites Engelmann had collected during the Utah

explorations--specimens that Meek described for the first time

in a peer-reviewed scientific paper in 1876, shortly before his

death. In the early 1870s geologist G. K. Gilbert, aware of Engelmann's

fossil discoveries, visited Antelope Spring and measured upwards

of 2,300 feet of middle Cambrian strata, collecting in the process

numerous trilobites subsequently identified and described by

famous Cambrian paleontologicst C. D. Walcott, who during expeditions

to Wheeler Amphitheater in 1903 and 1905 not only recovered additional

abundant fossil material, but also measured the entire middle

to late Cambrian sequence exposed in the general vicinity--a

sedimentary succession now known to contain the following geologic

rock formations: middle Cambrian Howell Limestone; middle Cambrian

Dome Limestone; middle Cambrian Swasey Limestone; middle Cambrian

Wheeler Shale; middle Cambrian Marjum Formation; middle Cambrian

Weeks Limestone; upper Cambrian Orr Formation; and upper Cambrian

Notch Peak Formation (uppermost part is lower Ordovician). Walcott

officially named what's now universally recognized as the world-famous

middle Cambrian Wheeler Shale in a scientific paper in 1908.

After Walcott's contributions, the proverbial paleontological

flood gates open on scientific exploration of the House Range

and its incomparable middle to late Cambrian geologic section;

scientific research papers now abound.

At Wheeler Amphitheater, only a rather narrow 17-foot thick

section in the upper portions of the middle Cambrian Wheeler

Shale produces significant concentrations of fossil remains.

This is the precise interval that's presently mined commercially

for paleontologic specimens, having operated more or less continuously

since the late 1960s when an enterprising entrepreneur recognized

that, fortuitously, the richest trilobite horizon occurred in

an easily accessible valley or "amphitheater" on Utah

state-owned lands, which could legally be leased for natural

resource exploitation.

While collecting within that specific 17-foot thick zone

of optimal trilobitic presence, fossil seekers catch on pretty

quickly that despite the common occurrence of exceptionally well

preserved trilobite exoskeletons in the rocks--most often discarded

arthropod molts, shed each time the animal underwent a spurt

of growth (identical to modern arthropod insects, crabs, and

spiders who during growth cycles regularly drop their old body

armor for newer external coverings)--only three species pop up

with any kind of regularity. These include Elrathia kingii

(the most famous trilobite in the world), Asaphiscus wheeleri,

and Peronopsis interstricta. Much rarer trilobite finds

invariably constitute carapaces of Bolasidella housensis,

Altiocculus harrisi (formerly Alokistocare harrisi),

and Olenoides nevadensis. Excluding casual surface collecting

atop the numerous spoils piles, searching for prize specimens

others might have left behind or overlooked (a method that often

discloses excellent material, by the way), the most efficient

collecting method is to attempt to split sizable shale chunks

along their original planes of sedimentary deposition with a

geology rock hammer/pick. An optional technique involves utilizing

a selection of well-tempered chisels in combination with the

rock pick.

What you'll find in both instances is that with a gentle,

firm rapping the trilobites tend to pop out of the rocks whole

and complete, often in an essentially perfect state of preservation.

This unusual style of fossil occurrence developed when dolomite

(magnesium carbonate) precipitated in the trilobite carapaces,

forming in effect "trilobite nodules" that only await

a patient collector to crack them free. Practical experience

has demonstrated here that on average most collectors find anywhere

from 10 to 20 trilobites in a four-hour period; the majority

of trilobites unearthed range from under an inch to two inches

in length. Occasionally a few specimens could reasonably require

special prepping with perhaps an abrasive air scribe, to remove

sedimentary particles that obscure key features of the trilobites,

although in actual fact most finds need little more than a careful

washing with water and a toothbrush. Sometimes, though, it's

aesthetically appropriate to retain trilobites in their natural

state of preservation--still residing along the bedding planes

of the middle Cambrian Wheeler Shale, where they dropped to a

tropical sea floor accumulating silty detrital particles some

505 million years ago.

At that distant middle Cambrian date, today's Wheeler Amphitheater

existed as unlithified marine muddy ooze at rather shallow depths

several miles off the northwestern coastline of an ancient continent

geologists call Laurentia--the paleo-precursor to what eventually

became North America--then situated slightly south of the equator

in what's today the southern Bay of Bengal, between India and

Thailand. Over the course of geologic time, continental drift

has carried the once-tropical trilobite beds northeastward thousands

of miles into the temperate latitudes of present-day North America,

where they now outcrop within the eastern reaches of the Great

Basin Desert.

Within the House Range geographic province, paleontologists

have identified some 35 species of trilobites from the middle

Cambrian Wheeler Shale, although such extinct arthropods aren't

the only fossil varieties waiting to be found. Also present in

less frequent numbers are brachiopods; echinoderms, including

an eocrinoid ("dawn crinoid") called Gogia;

Phyllocarids (a bivalve crustacean with only two known living

members)--including the extinct Brachiocaris and Pseudoarctolepsis;

such early siliceous sponges as Diagonella, Choia,

and Chancelloria; an early Chelicerate (horseshoe crabs,

sea spiders, and arachnids are living members) called Esmeraldella;

Naraoia, a so-called trilobitomorpha, or "soft-bodied

trilobite"; Anomalocaris, the largest predator of

the Cambrian seas; annelids (the worms), including famous Wiwaxia,

which was first described from the astounding middle Cambrian

Burgess Shale of Canada; and 20 species of non-mineralized arthropods

unrelated to trilobites--in other words, soft-bodied animal remains

rarely encountered in the fossil record.

In general, the soft-bodied fauna occurs in sedimentary

layers where skeletonized animals remain absent; why this is

so puzzled investigating paleontologists, until a recent taphonomic

analysis of the Wheeler Shale fossil beds disclosed that Elrathia

trilobite-dominated biofacies accumulated under dysaerobic conditions

(low oxygen levels) that allowed frequent bioturbation (organisms

burrowing through the unconsolidated muds)--fasciliating rapid

decomposition of soft tissues in the presence of greater oxygen

content--whereas the non-mineralized (soft-bodied) creatures

were preserved when decay-inducing bacterial activity and bioturbation

became restricted by anoxic sediments lacking oxygen.

I first visited Wheeler Amphitheater several years ago

during a three-week summer vacation with my parents to eastern

Nevada and western Utah. From our base camp at Baker Creek Campground

in Great Basin National Park, Nevada (campsite #16, by the way--elevation

roughly 7,500; Great Basin NP is a terrific place to visit when

exploring the world-class paleontology of Millard County) we

headed out to classic Wheeler Amphitheater in dad's old ruggedly

reliable 1979 American Motors Corporation (AMC) CJ7 jeep he'd

purchased in Olathe, Kansas. I recollect that we gassed up in

Baker, Nevada, grabbed a few snack items and associated carbonated

beverages (AKA, sodas), then moved out into the brilliant early

eastern sun along a lonesome stretch of asphalt. Probably we

spotted no more than three or four vehicles during the entire

journey through timeless expanses of eastern Great Basin Desert.

As navigator and lead research archivist for the Millard trek,

I kept all pertinent road maps and scientific documents close

at hand, prepared for quick inspection should contingency referencing

become necessary.

What I remember distinctly is that we found the correct

turnoff to Wheeler Amphitheater without difficulty. Easily spotted,

indeed. After maneuvering along a system of surprisingly well-graded

dirt roads through stupendous isolation, we reached our desert

destination bursting with keen anticipation of a joyful paleontological

adventure. We were not disappointed. For the next four hours

or so we moved about the commercial quarry with a fevered zeal,

splitting 505 million year-old middle Cambrian Wheeler Shale

to find within several excellently preserved Elrathia kingii

trilobites that popped out of their muddy matrixes whole and

intact with but a gentle rock hammer tapping. This was discovery

ecstasy.

505 million years earlier we would have been floating atop

a warm, shallow sea off the northwest coast of North America's

ancestral continental mass situated slightly south of the equator

at the southern end of today's Bay of Bengal, between India and

Thailand. With living trilobites below us, the sun shines roughly

four percent dimmer than at Wheeler Amphitheater in a sky whose

atmospheric carbon dioxide levels exceed an approximated 4,000

parts per million--at least ten times higher than CO2 readings

of earth's last 100 Recent years--and average temperatures approach

77 degrees Fahrenheit, 27 degrees higher than a little over a

half billion years hence. A look shoreward from the Cambrian

sea discloses a landscape devoid of vegetation and animal life--an

early Paleozoic scene reminiscent of portions of the Great Basin

Desert, as observed from a distance in a moving vehicle through

Millard County to Wheeler Amphitheater some 505 million years

later.

Part 2--Fossil Mountain

After visiting classic Wheeler Amphitheater to sample an

amazing concentration of trilobites in the middle Cambrian Wheeler

Shale, it's time for a rendezvous with Fossil Mountain in the

Ibex District--a regional Millard County locale named for a European

wild goat in the 1890s by English immigrant Jack Watson, who

established a post office on property he homesteaded a few miles

north of what later became known as Fossil Mountain, proper.

The abundant fossil organisms at Ibex and Fossil Mountain

occur in the roughly 485 to 470 million year-old lower Ordovician

Pogonip Group, an association of six distinct and easily identifiable

geologic rock formations. This major stratigraphic succession

can be traced throughout western Utah and extreme eastern Nevada

(the Pogonip Group of eastern California is composed of several

different formations), but nowhere is it as fossiliferous as

in the Ibex area, where silty carbonate beds several feet thick

often consist of nothing but exceptionally well preserved brachiopods,

gastropods, ostracods, trilobites, or echinoderms--each animal

type characteristically contributing its specific remains solely

to an individual shell bed, to the exclusion of all other invertebrate

varieties. Such technically termed monotypic shell beds are extensively

developed in the Pogonip at Ibex's Fossil Mountain, and the fossil-saturated

ledges can be followed for considerable distances.

I had long heard reports of the remarkable paleontologically

prolific formations of the Ibex District--had even viewed stunning

brachiopod specimens from the lower Ordovician Kanosh Shale exposed

there. Nevertheless, I was dutifully skeptical of the reportedly

extensive, bountiful fossil occurrences. Many times in the past

I'd been given "reliable" information about a rave-review

region, only to find out that it could not live up to its advance

billing. A fossil dealer at a mineral show once touted Ibex,

talking on and on about the unbelievable abundance of fossils

available there, but at the time I was busy researching another

specific locality and his credible recommendations went over

my head.

At a rock shop in Calico Ghost Town, in California's Mojave

Desert a few miles east of Barstow, the proprietor made a special

point of showing off his Millard County specimens, including

chunks of brachiopod material from Ibex that were beyond belief.

By now my interest in the region was solidifying, but there just

didn't seem to be any spare time to get away and properly explore

the place.

When at last I finally made the trip to Ibex, I was not

disappointed. As the well-worn saying goes, you have to see it

believe it. The rocks are relatively flat-lying, in a horizontal

bedding orientation, and erosion has created natural ledges along

these bedding planes. Fossil hunters can simply hike along the

strike of the strata--in other words, along the horizontal direction

of the rock layers--and pick of free-weathered fossils at will,

in addition to innumerable quality chunks of fossil-bearing limestones

and shales.

From personal experience, I can recall few Paleozoic Era

localities that have yielded such a profusion of excellent forms.

Midwestern exposures certainly come to mind. While I was residing

in eastern Kansas a number of years ago, I had the great fortune

to explore several of the abandoned rock quarries in the area.

These have penetrated late Pennsylvanian limestones and shales

approximately 305 million years old, in which a mind-boggling

diversity of beautiful specimens occur. One quarry just a few

miles outside of town came to be my very favorite--the single

finest Pennsylvanian Period fossil-bearing site from which I

have ever collected.

If that quarry happens to rank as the best Pennsylvanian

fossil locality, then there is no doubt that Fossil Mountain

at Ibex is the finest Ordovician Period fossil-yielding area

I have visited. It is true, of course, that I have yet to explore

the famous Ohio Ordovician outcrops.

Although Fossil Mountain of Ibex lies within a proverbial

no man's land--parched desert many miles from the nearest center

of population (that would be Delta, Utah)--the fossil-bearing

area is rather easily reached via a system of well-maintained

dirt roads. Still, this no place to become stranded. Make certain

that your vehicle is in perfect working order. Carry a well-maintained

emergency first aid kit, extra food, and plenty of water: The

traditional rule stresses that one must possess at least one

gallon of water per person per day in reserve for the duration

of an expected dry-camping expedition. And notify local authorities

in Delta--or, Baker, Nevada, if one is traveling to Millard County

from directions west--of your destination and how long you plan

to stay. But be sure to contact them when returning to civilization,

so they won't organize a rescue operation unnecessarily. While

in the neighborhood of Baker in White Pine County, eastern Nevada,

by the way, consider a visit to Great Basin National Park--established

October 27, 1986; beaucoup scenic wilderness adventures await,

and Baker Creek Campground at an elevation of roughly 7,500 feet

makes a most comfortable base camp during summer visits.

Those of us who travel the desert regularly sometimes develop

a lazy attitude toward these important reminders. I freely admit

that I have on occasion broken the rules of safe and sane backroads

travel conduct. Just call me lucky so far. So, don't do as I

do--as the saying goes--do as I say.

Note, too, that Ibex's Fossil Mountain presently lies within

the proposed King Top Wilderness area. This means that only surface

collecting of fossil specimens is allowed--do not dig into the

exposed strata; pick up and keep only what you find already lying

atop the ground. And before proceeding into the wilds, check

with the local Bureau of Land Management office (BLM) to determine

the latest land status. If the region eventually goes the route

of a federally protected wilderness, unauthorized amateur collectors

will likely incur additional restrictions on their hobby fossil-finding

activities. Obey all rules and regulations. For example, fossils

collected on America's Public Lands (administered by the BLM)

must never be sold or bartered--in legal argot, generally agreed

by common convention to mean that you can't trade for specimens,

either. Watch for BLM signs along the way that detail the latest

official public lands status.

After negotiating a system of decently maintained dirt

roads through several lonesome miles of classic Great Basin Desert

terrain, one arrives at excellent exposures of the lower Ordovician

Lehman Limestone--the first prominent and easily accessible outcrops

of the paleontologically prolific Pogonip Group one encounters

within view of looming Fossil Mountain, now less than two and

a half miles away. The rugged slopes to the right of the dirt

trail (north) consist of blue-gray-weathering arenaceous limestones

in which moderately common brachiopods, ostracods (a small bean

to pea-shaped bivalve crustacean), and gastropods occur. Yet

another paleontological point is that the first corals in the

local Ordovician Ibexian stratigraphic record happen to appear

in the Lehman Limestone.

This is an advantageous place to become acquainted with

the regional style of rock outcropping and fossil occurrences

in the Fossil Mountain/Ibex District. You will note that the

limestone layers here are essentially flat-lying, in what geologists

call a horizontal bedding attitude. Considering the extreme geologic

age of the Lehman Formation--some 470 million years old--the

lack of metamorphism and related deformation of the Ordovician

strata is absolutely astonishing.

The Lehman limestones tend to form prominent ledges, while

the shale partings have been eroded back in recess. This is the

distinctive geomorphological characteristic of all the exposed

early Paleozoic rock formations in the Ibex District. Not every

carbonate layer here is fossiliferous but, rather, the specimens

occur in specific zones or horizons throughout the sequence.

Some beds yield only ostracods, while others are packed with

brachiopods, echinoderms, trilobites, or gastropods.

The Lehman Limestone is the youngest of the six geologic

rock formations included in the geographically widespread lower

Ordovician Pogonip Group--roughly 485 to 470 million years old--which

reaches its most abundant and reliably diverse fossil development

at Fossil Mountain and the surrounding Ibex area. In descending

order of geologic age, this significant grouping of strata includes,

first, the Lehman Limestone, then the Kanosh Shale, the Juab

Limestone, the Wah Wah Limestone, the Fillmore Formation, and

the House Limestone. In general, all Pogonip rocks but the House

Limestone yield plentiful fossils. This is not to say that the

House is a disappointing unit; it's just that its ledges of silicified

trilobites are more difficult to spot in the field.

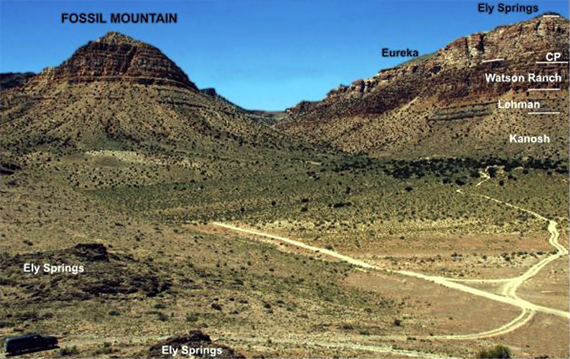

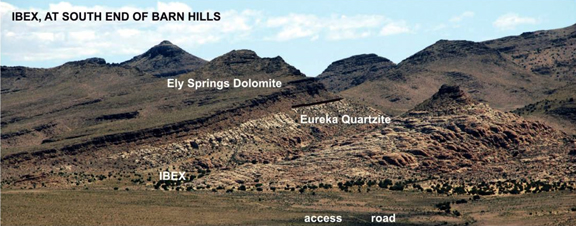

After examining the Lehman Limestone outcrops, one continues

along the primary dirt road to another branching dirt trail.

Which way to go to get to Fossil Mountain is now no longer even

a question. At this point Fossil Mountain--the primary fossil-bearing

locality in the Ibex District--looms to your immediate northwest,

a great pyramid-shaped protuberance composed of a conformable

(i.e., without any breaks in time in the geologic history of

sedimentary deposition) sequence of lower Ordovician through

middle Ordovician-age strata capped by the erosion-resistant

middle Ordovician Eureka Quartzite (not a member of the Pogonip

Group)--a massive accumulation of heat and pressure-altered sandstones

that are in large part responsible for the protection of the

fossiliferous limestones and shales below. They have prevented

the erosion of the less-resistant Ordovician rocks in much the

same manner that a small pebble resting atop a glob of mud will

keep the mud mound intact through a rainstorm, while soil exposed

to the brunt of the storm easily washes away.

Immediately below the brilliant white Eureka Quartzite

capstone on Fossil Mountain are two additional rock formations

geologists exclude from the early Ordovician Pogonip Group: The

darker band below the quartzite peak is the middle Ordovician

Crystal Peak Dolomite; and that bold, steep cliff face composed

of alternating white and brown bands is the middle Ordovician

Watson Ranch Quartzite, underlain in turn by a narrow, prominently

protruding limestone ledge belonging to the lower Ordovician

Lehman Limestone, the youngest member of the Pogonip Group. According

to several official geological measurements, early to middle

Ordovician-age rocks in Millard County accumulated to an aggregate

thickness of some 3,500 feet.

At the intersection with the north-south trending dirt

road that leads over to Fossil Mountain, you will note to the

right of the road a magnificent exposure of the middle Ordovician

Eureka Quartzite--the same geologic interval that caps Fossil

Mountain. This is certainly one of the most widespread early

Paleozoic Era rock units in all the Great Basin Desert. It has

been recognized as far away as eastern California, in the mountains

surrounding Death Valley National Park.

For decades, scientists have speculated on the original

environment of deposition of the Eureka Quartzite, an unusually

thick bed of heat and pressure-crushed sandstone. Many models

have been analyzed, but no one explanation seems to answer all

the questions.

The main problem for geologists is to satisfactorily account

for such a massive, persistently uniform zone of practically

pure metamorphosed sandstone that occurs over hundreds of square

miles. It hasn't been easy. After much debate on the subject,

earth scientists remain puzzled and intrigued, although recent

investigations seem to show that the Eureka Quartzite accumulated

some 465 million years ago as clean, well-sorted beach sand along

the shores of a shallow sea during the middle portion of the

Ordovician Period.

If this is true, the Eureka Quartzite could well represent

one of the oldest identifiable terrestrial rock deposits in North

American.

A short drive beyond the Eureka Quartzite exposure brings

you directly in front of the place you want to visit.

Before you rises Fossil Mountain, one the great early Ordovician

fossil-bearing sites in existence. It was named--and first popularly

publicized--sometime between 1910 and 1920 by Frank Ashel Beckwith,

a cashier at the first established bank in Delta, Utah, who spent

considerable spare time exploring the fossil wonders of Millard

County. Among a shipment of early Ordovician invertebrate fossils

that Beckwith donated to the US National Museum (part of the

Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C.), a selection of brachiopods

became the first paleontologic specimens from Fossil Mountain

ever formally described in the scientific literature (1936 and

1938); mysteriously, though, the paleontologists who wrote up

the papers failed to credit Beckwith as the donor.

A short walk toward Fossil Mountain will place you on the

ledge-forming, dark-blue silty limestones of the Wah Wah Limestone.

Silicified trilobites, algae-sponge patch reefs, conodonts (a

minute feeding apparatus, unrelated to modern jaws, from an extinct

eel-like organism--seen only in the insoluble residues of carbonates

dissolved in a dilute solution of acetic or formic acid), graptolites,

gastropods, brachiopods, solitary sponges, nautiloid cephalopods,

and cystoid echinoderms constitute members of a large and diverse

fossil assemblage.

The Wah Wah Limestone in the vicinity of Fossil Mountain

is about 235 feet thick. It is traceable southward from the parking

area for a little over a mile, and fossils can be collected throughout

this entire area of outcrop.

As in the Lehman Limestone explored earlier, the Wah Wah

specimens (yes, the Wah Wah is colloquially called "The

George Harrison interval, where all things Ordovician must pass"...)

tend to occur in distinct zones. This means that productive,

fossiliferous horizons are separated by many feet of barren limestone

and shales. The trick, naturally, is to locate these fossil-rich

ledges, then follow them as they arc about the hillsides.

As you ascend the slopes of Fossil Mountain, the Wah Wah

Limestone grades into the younger Juab Limestone, which consists

mainly of medium-gray arenaceous limestone that forms ledges

up to four feet thick. There are also minor interbeds of tan

shale in the sequence.

Despite the fact that the Juab is a relatively thin geologic

unit--only 160 feet at most--many fossil types are well-represented.

Brachiopods, gastropods, cephalopods, trilobites, conodonts,

solitary sponges, and graptolites are especially characteristic

of the formation.

Directly above the Juab Limestone lies the next-youngest

formation, which also happens to be the most fossiliferous lower

Ordovician Pogonip Group unit of them all--the fabulous Kanosh

Shale. Simply continue your hike upward along any of Fossil Mountain's

numerous erosion gullies and you will soon intersect the unmistakable

olive-brown to chocolate-brown shales that tend to form slopes

and protruding ledges.

Here you will discover a profusion of fossils--especially

orthid-type brachiopods which form beautiful museum-quality shell

beds (also called monotypic beds); these are accumulations of

prodigious quantities of a single species of brachiopod, only,

that typically form a great percentage of the rocks in which

they occur. Free-weathered brachiopods are abundant, as well--a

superior selection of plentiful pedicle and brachial valves,

plus fully articulated specimens with both valves preserved intact.

Researchers suggest that such Kanosh Shale monotypic shell

beds developed under supremely stressful paleo-environmental

conditions, probably when early Ordovician marine saline levels

rose to critical concentrations, initiating "brachiopod

blooms;" the brachs reacted to the increasingly intolerable

alteration of a once-salubrious sea geochemistry with adaptive

creativity; they opted to over-reproduce in sudden spurts, saturating

the Ordovician sea floor with great numbers of their kind, ensuring

that at least a few would persist and endure. On occasion, though,

the periodic prolific brachiopod blooms were ultimately overcome

by rapidly deteriorating conditions that proved fatal, and so

entire beds composed mostly of their multitudinous valves built

up on the sea floor.

Other fossil groups well represented in the Kanosh Shale

include ostracods--which often form their own impressive monotypic

shell beds--gastropods, bryozoans, cephalopods, pelecypods, graptolites,

echinoderms, sponges, conodonts, and trilobites. Many Kanosh

Shale bryozoans and echinoderms originally inhabited what paleontologists

call hardgrounds: that is, sections of the Fossil Mountain sea

floor created when early Ordovician storm waves exhumed abundant

inorganically precipitated calcareous nodules, forming discrete,

extensive beds of so-called "marine pavement." Upon

these newly developed areas early echinoderms (often, a rhipidocystid

eocrinoid) found a favorable environment to proliferate, contributing

when they died vast numbers of disassociated ossicles (also called

"stems" or columnals) and holdfasts--the minute, bulbous

attachments that allowed the animals to anchor themselves--to

the ever-thickening cemented substrate. Repeated echinoderm death

cycles created ever-expanding space for an even more diverse

echinoderm fauna to thrive, atop which, eventually, several species

of bryozoans came along to help colonize the hardgrounds areas,

as well--the first known bryozoans in the fossil record to inhabit

hardgrounds, which are also known from the preceding Cambrian

Period that ended some 10 million years before the Kanosh Shale

began to accumulate, a time prior to 485 million years ago when

only echinoderms contributed to hardground developments on the

early Paleozoic sea floors. So scientificially fascinating are

the Fossil Mountain examples that paleontologists and geologists

from all around the world travel to Millard County, Utah, to

study the classic Kanosh Shale hardgrounds.

This is a formation absolutely packed with wonderfully

preserved fossil material. Like others before me, I could rave

on and on about the excellence displayed here, the diversity

of early Ordovician animal groups and the quality of their preservation,

but you too will just have to see it to believe it. The Kanosh

Shale, with its fantastic brachiopod and ostracod shell beds,

early echinoderm-bryozoan hardground developments, and prolificly

diverse free-weathered invertebrate animal fauna, ranks as one

of the most important paleontologic exposures in North America.

To collect here is an exhilarating, uplifting experience--one

I will never forget.

The older Fillmore Formation and House Limestone are not

exposed on the immediate slopes of Fossil Mountain, but typical

fossiliferous outcrops can be found not far from the parking

area. There, the Fillmore is roughly 1,600 feet thick, consisting

of interbedded conglomerate, olive-gray to greenish shale, fine-grained

limestone, and occasional lenticular algae-sponge patch reefs;

other fossils present include graptolites, trilobites, brachiopods,

conodonts, gastropods, echinoderms, and cephalopods. Oldest of

the Pogonip Group formational subunits, the lowermost Ordovician

House Limestone yields silicified trilobites and brachiopods

through approximately the upper third of 500 feet of finely crystalline

limestone in beds two to four feet thick.

My first visit to the Ibex District provided me with an

extraordinary collection of early Ordovician invertebrate animal

specimens. I only wish I could have stayed longer.

While exploring the gullies and dry washes at Fossil Mountain,

I felt incredibly privileged to be collecting from such a remarkable

series of fossil-bearing geologic formations. They were deposited

some 485 to 470 million years ago in a warm shallow sea then

situated astride the equator--a deep time tropical ocean that

teemed with burgeoning early Paleozoic Era life. That varied

life of the early Ordovician has now been preserved in splendid

detail at Fossil Mountain, where neither the ravages of erosion

nor the brute force of metamorphism has harmed the ancient animals.

They now reside in the limestones and shales of a vanished age--kept

alive in their death for nearly half a billion years, longer

than the human mind can comprehend. The abundant and beautifully

preserved fossils at Ibex give us a rare glimpse back in time

to a unique association of animal life that will never exist

again.

|