| Text: The Field Trip | Images: On-Site | Images: Fossils | Widget: DV Weather |

| Links: My Music | Links: My Fossils Pages | Links: USGS Papers | Email Address |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. The view is roughly southward through Lost Burro Gap in Death Valley National Park, California--one of three superior occurrences of the much famous fossil-bearing Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Formation discussed in the field trip text, below: Two of the Tin Mountain sites lie within Death Valley National Park, while a third resides on Bureau of Land Management (BLM)-administered public lands and is open for hobby collecting of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossils. In the photograph, the paleontologically significant 358.9 to 350 million year-old Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone is the darker interval, to skyline, above the lighter-colored dolomites of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation that extend to road level. The Tin Mountain here contains great quantities of colonial tabulate corals, colonial hexacorals, solitary horn rugose corals, brachiopods, bryozoans, and crinoids. Keep all that you find here only in a camera, of course. Photograph courtesy "Destination4x4." |

|

One of the most persistently fossiliferous geologic rock formations in all the western Great Basin Desert wilds of Inyo County, California, is the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone, a classic carbonate accumulation that has yielded an abundance of well-preserved invertebrate animal remains 358.9 to 350 million years old--including such major groups as brachiopods, bryozoans, conodonts (minute phosphatic tooth-like structures, unrelated to modern jaws and teeth, that served as a unique feeding apparatus in an extinct lamprey eel-like organism), corals, mollusks (gastropods, pelecypods, and ammonoid cephalopods), ostracods (diminutive bivalved crustaceans), and trilobites. It was first named in the scientific literature, appropriately enough, for its prominent exposures on Tin Mountain in then Death Valley National Monument (now of course it's situated within the confines of Death Valley National Park, as of 1994), the northernmost peak in the Cottonwood Mountains around 12 miles southwest of Scotty's Castle (as the crow flies). While the outcrops there are obviously off-limits to unauthorized amateur collecting, other amazingly fossiliferous exposures of the mid Paleozoic Era formation that occur outside the park's boundaries on Bureau of Land Management (BLM)-administered public lands remain wide open for hobby gathering of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossils. But here is where the proverbial fun begins. Despite the fact that the Tin Mountain Limestone is a widely distributed and distinctive rock unit exposed throughout the mountains bordering Death Valley, easily accessible outcrops remain tantalizingly few and far between. And even if collecting were allowed within the national park, one problem would still remain to be solved: how to reach the fossiliferous strata without incurring injury, since many of the especially promising outcrops that I've observed occur along the skylines of steep ridges where access to the potential paleontology present there would probably demand sophisticated mountain-climbing techniques--boo, hiss. This circumstance is definitely most discouraging, in the main. Yet all is not lost. Happily, through persistent geological and paleontological due diligence (consulting geologic maps and old United States Geological Survey reports, primarily), Tin Mountain aficionados--a rather loose-knit association of interested invertebrate animal enthusiasts, as it were--have identified for inspection three easily accessible, representative exposures of the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone, where visitors can sample innumerable photogenic fossil specimens stained an aesthetically attractive reddish-brown on a dark blue limestone matrix. Even though two of the prime fossil localities admittedly lie within the borders of Death Valley National Park--a third site happens to reside on public lands and is wide open for hobby fossil acquisition--seekers of exceptional Tin Mountain paleontology nevertheless continue to frequent with considerable consistency those places still under jurisdiction of the National Park System. The reasons for this behavior are not difficult to identify, of course: Combining a Death Valley scenic adventure with an opportunity to take photographs of some special Paleozoic Era fossils is an irresistible attraction, indeed. A first Tin Mountain Limetone site occurs in the vicinity of Towne Pass, which used to lie just outside the western boundary of Death Valley National Monument; it's now well within territory that is federally mandated as a national park. Prior to 1994, though, when the Desert Protection Act became law--assimilating in one fell swoop millions of acres of adjacent wilderness lands into a newly created Death Valley National Park system, the legendary Towne Pass locality could be found with happy convenience but a literal stone's throw outside Death Valley National Monument. As a consequence, it was a very well known and productive fossil locality, one that furnished generations of amateur paleontology enthusiasts and professional Earth Scientists alike with myriads of beautiful Early Mississippian fossil forms. Towne Pass used to lie two-tenths of a mile southwest of the entrance to Death Valley National Monument, but it presently resides wholly within the confines of Death Valley National Park along California State Route 190, 60.3 miles east of its junction with US 395 in Olancha (Owens Valley). Elevation is 4,956 feet here--it's indeed the final major grade one encounters before the plunge into Death Valley, proper, on the eastern slopes of the Panamint Range. A faint dirt trail which connects with RS 190 but a few feet downgrade from Towne Pass provides a convenient place to park off the main road. The fossiliferous Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone beds occur about three-quarters of a mile almost due east of Towne Pass. A relatively non-strenuous hike across a gradually ascending alluvial fan is necessary to reach them. To gain a general overview of the fossil-bearing area, stand next to the signpost at Towne Pass and look to the southeast, to the right side of the state route as it heads toward Death Valley. Navigationally speaking, the Tin Mountain outcrops occur 4,200 feet south, 65 degrees east of Towne Pass. But you don't need to drag out the sextant or the trusty Brunton compass to find out where to hike. As you look southeast from Towne Pass to the moderately steep ridge nearest route 190, you will note three distinct types of rocks exposed. At the northermost end of the ridge is a poorly stratified reddish-brown material banked against a thick wedge of cliff-forming dark blue limestone which in turn overlies a narrow band of light gray dolomite situated farthest south in the sequence. The reddish-brown sediments lying to the immediate north of the dark blue limestone and light gray dolomite are what geologists call a fanglomerate, a kind of fossilized alluvial fan deposited three to six million years ago during Late Miocene through Upper Pliocene times. It was derived from eroding Paleozoic Era sedimentary material exposed during the rather "recent" geologic uplift of the Panamint Range. It's a consolidated, cemented accumulation of pebbles, cobbles, and boulders weathered out of every Paleozoic rock formation present in the Panamints--a stratigraphically significant "layer cake" that faithfully records a mostly uninterrupted, conformable sequence of continuous sedimentary deposition dating from the earliest Cambrian Period, some 541 million years ago, all the way up to the conclusion of the Paleozoic Era, around 252 million years ago. That fanglomerate is truly fascinating in a strict geologic context, but it's obviously unfossiliferous (except for weathered chunks of organic-bearing sedimentary rock out of their normal stratigraphic position). Two-tenths of a mile south of the later Cenozoic fanglomerates lies the relatively narrow interval of pale gray dolomites--rocks belonging to the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation, 393 to 359 million years old, which is one of the most immediately recognizable rock formations in all of Inyo County. Locally it yields abundant reef-like accumulations of tangled stromatopoids, an extinct variety of calcareous sponge that experienced its greatest adaptive success during the Devonian Period. Additional Lost Burro fossil material includes spirifer-style brachiopods, corals, and Orecopia genus gastropods. Typical stromatoporoid types encountered in the Lost Burro include what porifera specialists call genus Amphipora--though it's more often referred to colloquially as the "spaghetti stromatoroid" because it usually resembles strands of pasta when spotted in the rocks--and a "bulbous" to conically configured variety with distinctive concentric laminations. Sandwiched between the grayish dolomite of the Devonian Lost Burro Formation to the south and the reddish-brown Upper Miocene to Upper Pliocene fanglomerate to the north is the material you want to explore for fossils--the bluish cliff-forming carbonates of the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. From the parking area at Towne Pass, hike the roughly three-quarters of a mile to the base of the limestone slopes, where several obvious mound-like accumulations of talus--eroded chunks of limestone brought down from the steep outcrops above--provide the most effective and efficient opportunities for productive fossil-finding. Remember, of course, that this spot lies within Death Valley National Park. Keep all that you find only in a camera. Search carefully through the limestone rubble outwash, watching in particular for brachiopods and corals--two of the more abundant invertebrate kinds present here. Spirifer-type brachiopods are very conspicuous, as are numerous specimens of such extinct corals as the colonial Lithostrostrotionella (a hexacoral), Zaphrentites (rugose horn coral), Caninia (a second type of rugose horn coral), and the colonial Syringopora (a colonial tabulate coral--often referred to as the "spaghetti coral"). All of the specimens here are rather easily spotted on the surfaces of the Tin Mountain carbonates; typically they stand out in bold brownish relief against the dark blue limestones. Many of the corals reveal exquisite external preservation, appearing almost lifelike in their internment in the rocks. The fossil-bearing horizons in the Tin Mountain Limestone accumulated some 358.9 to 350 million years ago along a shallow marine shelf then situated astride the equator, where optimal equable environmental conditions favored a genuine proliferation of invertebrate animal life. Based on the regional distribution of Paleozoic Era paleontology throughout Inyo County, paleo-geographers calculate that the Early Mississippian shoreline existed many miles southeast of present-day Death Valley. Probably there were several Madagascar-like large island land masses scattered in the general vicinity of where the Tin Mountain Limestone accumulated in a warm, relatively shallow tropical sea setting through Early Mississippian geologic times. After exploring the prolific paleontology at Towne Pass, it's time to visit probably the most accessible exposure of Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone in all of Death Valley National Park--incomparable Lost Burro Gap in the Cottonwood Mountains, several miles north of world-famous Racetrack Playa (site of those mysterious sailing stones), where you can actually drive right up to it in the field and then hop out of your vehicle and literally stand right next to Tin Mountain's geologic contact with the underlying dolomites and quartzitic sandstones of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation. Lost Burro Gap, as a matter of fact, is the very place that reinvigorated my enthusiasm for Paleozoic Era fossils--my first paleontological interest; a visit with my parents, as a kid, to California's Marble Mountains trilobite quarry in the Lower Cambrian Latham Shale started my life-long fascination with paleontology. After not a few years of concentrating primarily on Cenozoic Era terrestrial fossil deposits (paleobotanical, paleoentomological, paleomalacological, and vertebrate-bearing localities), a chance spur-of-the-moment decision to take a detour through Lost Burro Gap while heading south to the Racetrack Playa provided a serendipitous opportunity to rekindle my Paleozoic passions. Lost Burro Gap is indeed special. It preserves a remarkably representative geologic example of the same variety of mid Paleozoic Era strata one finds exposed throughout the western United States; rocks of roughly similar lithologies and of identical age can be traced all the way across the Great Basin, from the Inyo Mountains, California (west of Death Valley), clear through Nevada to western Utah, then north to Idaho and Montana (where the Lower Mississippian Lodgepole Limestone of the Madison Group is in part a correlative geologic time equivalent of the Tin Mountain Limestone). Here's a great opportunity, then, to examine fossiliferous rocks of Silurian, Devonian, and Early Mississippian age that record approximately 93 million years of passing geologic time. Not only is the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone easily prospected there for its abundant paleontology (remembering of course to take only pictures of the specimens), but the underlying Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation and Lower Silurian to Lower Devonian Hidden Valley Dolomite also contain bountiful silicified preservations of invertebrate animals (that is, replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide) The way to Lost Burro Gap is pretty straightforward, of course. A preliminary necessity for staging purposes is travel to the northernmost terminus of State Route 190 in Death Valley National Park. Take the route to Ubehebe Crater and Racetrack Playa. You will need a sturdy and reliable vehicle to negotiate safely the occasionally rough road up ahead. From the junction with SR 190, proceed 28 miles to Teakettle Junction. Here, Racetrack Playa with its world-famous sailing stones lies only seven miles farther south. Save that visit for another time, please. Proceed left on the branching dirt trail that leads to Hunter Mountain. Lost Burro Gap, proper, begins roughly one and a quarter miles from the intersection with Teakettle Junction. For approximately three-quarters to one mile the dirt path slices through spectacular exposures of the pale gray dolomites and brownish quartzitic sandstones of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation, capped by medium to dark blue carbonates of the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. At the southernmost reaches of Lost Burro Gap, extending onward into the hills surrounding Hidden Valley, easily accessible and representative outcrops of the Lower Silurian through Lower Devonian Hidden Valley Dolomite occur. All the geologic rock formations at Lost Burro Gap offer ample chances to examine nicely accessible mid Paleozoic Era paleontology (that is to say--fossils of Silurian, Devonian, and Mississippian age). Just about any gully there, for example, leads you to within reach of the Tin Mountain Limestone, while the Lost Burro Formation and Hidden Valley Dolomite are for the most part exposed within immediate reach on both sides of the road. At the southern end of Lost Burro Gap, the Tin Mountain Limestone dips down to road level in direct geologic contact with the older underlying Lost Burro Formation, and you can get out of your vehicle, right on the spot, and stand at the precise moment in geologic time when the Devonian changed to the Mississippian Period 358.9 million years ago. In the Lost Burro Gap district, the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone is quite fossiliferous. It's roughly 475 thick here, divisible into two main members based on a general aspect of outcropping, variations in limestone bedding, and relative prevalence of interstratified shales. The lower unit, for example, is a bench to mild slope-forming unit roughly 275 feet thick--a medium gray limestone preserved in beds two to six inches thick, separated by thinner layers of calcareous shale in shades of light brownish-gray to pale red; dark gray chert nodules are occasionally encountered. Above that is member two's 200 feet of cliff-forming, erosion-resistant medium gray limestone in beds a few inches to two feet that bear a few dark-gray chert nodules; pale-red shale parting are faint, few and far between. Fossils occur throughout the full 475 feet, but the best material can be observed in the lower bench-forming unit, where limestone beds composed almost entirely of crinoid stems (technically termed an encrinite) lie juxtaposed stratigraphically with carbonates crammed with tabulate "spaghetti" Syingopora corals, rugose horn corals, and wildly branching favositoid corals. Brachiopods are common, and diverse. Expect to encounter such genera as Shumardella, Spirifer, Brachythyris, Composita, Productella, Schizophoria, and Punctospirifer. Lying in conformable stratigraphic position below the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone is the Middle Devonian to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation, originally named in the scientific literature as a matter of fact for its occurrence here at Lost Burro Gap. It forms virtually all of the eye-catching sculpted walls of Lost Burro Gap closest to the main road. With minor lithologic variations, the Lost Burro is a great accumulation of some 1,500 feet of dolomite (magnesium carbonate), sandy dolomite, quartzitic dolomite, and limestone characterized by dramatic banded bedding in alternating shades of pale gray to dark blue and almost black. In a roughly 530 foot thick interval of dark gray to almost black limestones and dolomites near the middle of the Lost Burro, myriads of interesting stromatoporoids--an extinct variety of calcareous sponge that often dominated Devonian marine ecosystems--occur as tangled masses of "spaghetti"style "strands" of Amphipora and associated concentrically laminated hemispherical to conical examples; all quite photogenic, indeed. Near its contact with the overlying Tin Mountain Limestone, the upper 35 feet of the Lost Burro Formation consists of a brown and pinkish-brown weathering shaly quartzitic dolomite which produces stunning specimens of the spirifer-type brachiopod Eleutherokomma. Additional Late Devonian brachiopods from the uppermost Lost Burro beds include Tylothyris cf T. raymondi Haynes, "Camarotoechia" aff. "C" doplicata (Hall), Cleiothyridina cf C. devonica Raymond, and Productella. Resting in geologic contact directly beneath the Lost Burro Formation is the Lower Silurian to Lower Devonian Hidden Valley Dolomite, named in the technical literature for its typical exposures in Hidden Valley just south of Lost Burro Gap. That's where it reaches its ultimate development, its thickest and most representative style of outcropping--some 1,300 feet of a medium gray and light gray magnesium carbonate. At the southernmost reaches of Lost Burro Gap, lying along the west side of the road in particular, a conveniently accessible exposure of the fossiliferous Hidden Valley can be examined. Here one may observe in situ many nice examples of Silurian corals from the lower section of the Hidden Valley Dolomite, including--globular Favosites; solitary tetracorals; "spaghetti" Syringopora tabulate corals; and the important Index Fossil Halysites, more commonly called a tabulate chain coral. Halysites is classically diagnostic of Ordovician and Silurian-age rocks worldwide, though it's most especially characteristic of Silurian deposits. In strata nearly transitional with the overlying Lost Burro Formation, from a 65-foot thick section of medium gray dolomite that tends to weather light olive gray, the Hidden Valley yields several quality Early Devonian fossil varieties--including cup corals; a rugose coral called Papiliophyllum elegantulum; two species of tetracoral--Amplexus lonensis and A. invaginatus; Cladopora favositid corals; Heliolites tabulate corals; Platyceras gastropods; and the brachiopod Acrospirifer kobehana. Of particular interest to coral specialists is the reported occurrence in the Hidden Valley Dolomite of beautifully preserved rugose "button corals" called scientifically Porpites porpita. Also described--from Hidden Valley carbonate samples dissolved in a diluted solution of acetic acid (by technicians who've secured a collecting permit from the National Park Service)--are abundant conodonts, minute tooth-like structures (unrelated to modern jaws or teeth) that acted as a unique feeding apparatus in an extinct lamprey eel-like organism. After fossil-prospecting Lost Burro Gap (with a camera in hand, of course--no need to recapitulate NPS rules and regulations, I reckon), it's time to head on over to a third accessible Tin Mountain fossil-bearing area. It lies on public lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and is therefore open to the hobby fossil collecting of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate animals. This third locality lies in the Funeral Mountains outside Death Valley National Park. Here in the Funeral Range, geologists and paleontologists have probably conducted their most exhaustive scientific investigations of the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. Most authors mention in their formal reports that the Tin Mountain here is exceptionally fossiliferous with corals and brachiopods and crinoids and conodonts and foraminifers and ostracods in particular from a measured section some 315 feet thick. In the Funeral Mountains fossil area, the Tin Mountain is divisible into five mappable lithologic subunits, or members, which rest in conformable relations on the underlying Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation--a predominantly dolomitic deposit (composed of magnesium carbonate) that contains locally abundant Amphipora "spaghetti" and concentrically laminated hemispherical stromatoporoids, an extinct calcareous sponge--in addition to brachiopods, corals, crinoidal debris, and the remarkable gastropod Orecopia. At the Funeal Range site, the Tin Mountain Limestone rests with dramatic lithologic and color contrast directly above the massive pale gray dolomites of the Devonian Lost Burro Formation. The lowest of the five Tin Mountain units (usually referred to as t1 through t5), is about 25 feet of interstratified medium dark gray limestone, shale, and argillaceous limestone that produces many corals, brachiopods, foraminifers, and conodonts. Above that lies about 75 feet of member 2 (t2), a medium dark gray limestone that weathers to shades of medium gray; brachiopods are common near the base of t2, while corals become more abundant toward the top, with microfossils--foraminifers and conodonts--associated with both the brachiopods and coelenterates. Relative prevalence of corals in unit t2 is best judged by the fact that all five of the following forms show up in most collections secured from it: Rylstonia, Homalophyllites, Syringopora, Vesiculophyllum, and Caninia. Next youngest Tin Mountain Limestone member is unit t3--usually described by field geologists as roughly 75 feet of coarsely bioclastic crinoidal limestone, crammed with large crinoid columnals and impressively robust disarticulated segments, that weathers to a distinctive light gray band along the mountainsides, in contrast with the darker blue carbonates immediately above and below it. Indeed, the unit produces some stunning crinoidal echinoderms that make attractive showcase specimens. Corals and brachiopods occur more commonly near the base and top of t3, in the dark to medium gray to limestones more characteristic of the formation. Unit t4 generally forms a 50 foot thick rubble-strewn bench below the steeper slope or cliff of the youngest Tin Mountain Limestone unit t5. T4 is a medium gray or darker limestone that contains distinctive pale-red, pinkish gray silty partings in its lower sections, while reddish argillaceous intervals tend to characterize the upper horizons. Numerous elongated chert nodules that almost coalesce with one another typify the upper limestone layers. Conspicuous unbroken fossils occur throughout the member. Obvious silicified organic constituents (replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide) include gorgeous coral heads, fantastic lattice-style bryozoans, and numerous species of beautiful brachiopods. Microfossil collections (recovered from a diluted acid solution) disclose abundant conodonts and ostracods. Goniatites ammonoids have also been reported here. Above the fabulously fossiliferous (t4) lies the steep slope or often cliff-forming limestones of member 5 (t5). Compared with the extraordinary diversity and richness of well preserved prolific paleontology exhibited by t4, member t5 could at first blush be considered a disappointing experience. This is fully expectable, in the main, one must admit. For one, t5's brachiopods and corals are usually less plentiful and not nearly as well preserved as their counterparts in the older underlying Tin Mountain unit. Still, some dedicated searching eventually discloses a satisfying assortment of fossil goodies from t5. Of course, by this time one really needs to watch one's footing, as the terrain becomes increasingly treacherous to try to explore. The steeper slopes reliably inhibit enthusiastic examinations of member 5, and probably this dramatic incline increase contributes to its under-reported fossil content. Because of its fortuitous accessibility in such proximity to the world-class geology and paleontology of Death Valley National Park, the Tin Mountain Limestone locality in the Funeral Range remains a seasonally popular destination for any number of university Earth Science field classes--primarily during the traditional field trip months of early Spring and mid Fall when meteorological conditions in tbis part of the Northern Hemisphere most reliably favor a comfortable outdoor experience. Probably not all of Tin Mountain's potential paleontological treasures will be spotted at the three sites visited here, but it is certainly stimulating to consider for future paleo-prospecting reference that even a partial listing of Early Mississippian invertebrate forms documented from its regional Death Valley area of outcropping includes the following: Foraminifers--Latiendothyra of the group L. parakosvensis, Palaeospiroplectammina aff. P. parva (Chernysheva), Septaglomospiranella primaeva; Corals--Amplexus sp., Aulopora sp., Beaumontial sp., Caninia sp., Cyathaxonia sp., Enygmophyllum sp., Homalophyllites sp., Lithostrotionella sp., Menophyllum sp., Rylstonia sp., Syringopora surcularia Girty, Syringopora aff. surcularia Girty, and Vesiculophyllum sp.; Bryozoans--branching bryozoans, indet., Cystodictya sp., Fenestella sp.; Brachiopods--Buxtonia sp., Camarotoechia sp., Chonetes sp., Cleiothyridina cf. (C. obmaxima (McChesney), Cleiothyridina sp. Composita, sp. Cyrtina sp. Dielasma sp., orthotetid brachiopod, genus indet., Productella sp., Punctospirifer sp., Rhipidomella sp. aff. R. michelini (Leveille), Rhynchopora sp., Scizotfhoria sp., Spirifer sp., (centronatus-type), Spirifer sp., terebratuloid brachiopod, genus indet., Torynspirifer sp.; Pelecypods--Allorismal sp., Parallelodonl sp.; Gastropods--cf. Anomphalus sp., Baylea sp., Bellerophon sp., Lanthinopsis sp., cf. Loxonema sp., Mourlonia, sp., Murchisonia sp., Naticopsis sp., Platyceras (Platyceras) sp. pleurotomarian gastropod, genus indet., Rhineoderma sp., Straparollus (Euomphalus) utahcnsis, (Hall), Straparollus (Euomphalus) subplanus (Hall and Whitefield), Straparollus (Euomphalus) sp., indet. subulitid gastropod, genus indet.; Cephalopods--goniatite cephalopod, undet. orthoceroid cephalopod, undet.; Trilobite--phillipsid trilobite, genus indet.; Worms (phylum Annelida)--cf. Spirorbis sp.; Conodonts--Siphonodella cooperi Hass, S. obsoleta Hass, Polygnathus symmetricus E. R. Branson, P. inornatus E. R. Branson; Ostracods--Tetrasacculus sp. aff. T. stewartae Benson and Collinson, Amphissites n. sp. aff., A. similaris Morey, Roundyella, n. sp. aff. Scrobicula crestiformis Kummerowia, n. sp. aff. Kirkbya fernglennensis, Kummerowia, n. sp. aff. Kirkbya keiferi, Kirkbyella (Berdanella) n. sp. aff. Kirkbyella annensis Benson and Collinson, K. B., n. sp. aff. K. recticulata Green, Psilokirkbyella ozarkensis (Morey), Rectobairdia sp. cf. R. confragosa Green, Acratia (Cooperuna), n. sp. aff. A. similaris Morey Green, Bohlenatia, n. sp. aff. Acanthoscapha banffensis Green, Monoceratina, n. sp. aff. M. virgata Green, Monoceratina n. sp. aff., M. elongata Benson and Collinson, Graphiadactylloides, n. sp. aff. Graphiadactyllis moridgei Benson. Theoretically, at least, all three Tin Mountain Limestone localities can be visited in reconnaissance style in a single day. That would of course entail quick flitting from place to place, spending but a perfunctory period at each paleo-treasure area. A more leisurely adventure scenario of relaxed exploration is obviously advocated here. Finding a place to spend a few days in this Great Basin Desert region is certainly not a difficult proposition. The primary campgrounds within Death Valley National Park are situated at Mesquite Spring, Stovepipe Wells, Furnace Creek Ranch (Sunset and Texas Spring campgrounds), and Panamint Springs Resort (about 13 miles west of the Towne Pass Tin Mountain fossil site). Cabins can also be rented at Panamint Springs, and motel rooms are available at Furnace Creek Ranch. Once outside the boundaries of Death Valley National Park on public land, you are permitted to choose just about any camping place that strikes the fancy. If all else fails, excellent accommodations can be found at Beatty, Nevada, or even Lone Pine, California. Here's an opportunity to journey back in deep geologic time to a tropical Tin Mountain Limetone sea teaming with Early Mississippian life. That reefs of corals and other creatures flourished at the equator here some 358 million years ago in a warmwater ocean in what is today a supremely dry Death Valley area desert seems incalculably improbable. Yet, in the Great Basin Desert of eastern California--at Lost Burro Gap, the Funeral Range, and a site within view of Towne Pass--you can stand at the equator of gone time, of 358 million years ago, and witness the vanished animals living on in stone all around you. |

| Towne Pass Locality | Lost Burro Gap Locality | Funeral Range Locality |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. A Google Earth street car perspective that I edited and processed through photoshop. The view here is southeast from Towne Pass along State Route 190 in Death Valley National Park, California, to Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone exposures that are within hiking distance of about three-quarter mile. That "small" reddish-brown patch at the base of the peak in upper center is where you'll find beaucoup nicely preserved invertebrate fossils in weathered rubble from Tin Mountain limestones, some 358 million years old, brought down by erosion from exposures higher up on the slopes. Before Death Valley became a national park in 1994, the locality existed outside of Death Valley National Monument on Bureau of Land Management (BLM)-administered public lands and was wide open for hobby collecting of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossils. Remember, of course, that the locality now lies within a national park. Keep all fossils found in a camera. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. An explorer of the Early Mississippian tropical sea in Death Valley stands at Towne Pass in Death Valley National Park. He is ready to hike the three-quarters mile to that "small" reddish brown patch at the base of the mountain at upper right. That's where excellent silicified (replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide) remains of corals, brachiopods, crinoids, and bryozoans--among other major groups--can be observed in situ in the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. Whitish-gray strata in upper left half of image (part of it is above the individual's head) belong to the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation. Before Death Valley became a national park in 1994, the locality existed outside of Death Valley National Monument on Bureau of Land Management (BLM)-administered public lands and was wide open for hobby collecting of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossils. This photograph, by the way, was originally snapped with a Minolta 35mm camera. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. That reddish-brown limestone at top of image is the same "small" patch at the base of the mountain, seen in previous two photographs. It's roughly three quarters of a mile from the parking spot at Towne Pass along State Route 190. The rubble accumulation here is composed of limestone chunks weathered out from exposures of the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone higher up the slopes. Here can be observed numerous quality invertebrate animal fossils--including corals, brachiopods, crinoids, and bryozoans. Before Death Valley became a national park in 1994, the locality existed outside of Death Valley National Monument on Bureau of Land Management (BLM)-administered public lands and was wide open for hobby collecting of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossils. This photograph, by the way, was originally snapped with a Minolta 35mm camera. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. This is spectacular Lost Burro Gap in Death Valley National Park, California--scene of a truly classic mid Paleozoic Era stratigraphic section that includes the Lower Silurian to Lower Devonian Hidden Valley Dolomite, Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation, and the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. Lower paler-colored exposures through which the dirt path runs belong to the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation--here a massive accumulation of dolomite (magnesium carbonate), sandy dolomite, and quartzitic dolomite locally fossiliferous with stromatoporoid sponges, brachiopods, and crinoidal material. The extraordarily fossiliferous Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone is the darker-colored slope about three-quarters the way up the slope at left, forming the entire skyline within this view. The Tin Mountain provides Paleozoic seekers with loads of corals, brachiopods, crinoids, bryozoans, and mollusks (gastropods, pelecypods, and ammonoid cephalopods). This photograph, by the way, was originally snapped with a Nikon 35mm camera. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Both photographs shot at Lost Burro Gap in Death Valley National Park, California. Left to right--A desert adventurer--my late father--stands on the west side of Lost Burro Gap at the exact contact between two Paleozoic Era geological periods. The brownish outcrop at lower right lies at the very top of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation; it is therefore very latest Devonian in geologic age. Behind my father, everything within view lies in the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. Geologic age of the precise point where my father stands is 358.9 million years--transitional Devonian to Mississippian age. Right--The individual is probably difficult to spot, but he's standing at roughly three-quarters the way up the slope at the geologic contact between the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation; everything from where he stands down to ground level is the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation everything above him, to the skyline, is the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. Both photographs, by the way, were originally snapped with a Nikon 35mm camera. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. At Lost Burro Gap in Death Valley National Park, California. Note the seeker of mid Paleozoic Era paleotology up on the "bench," about three quarters the way to top of the photograph. He is standing in the latest Devonian section of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation, several feet below its contact with the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone (all darker colored rocks to the skyline above the reddish-brown zone roughly three quarter the way to top of image). That upper few feet of the Lost Burro Formation here consists of a brown and pinkish-brown weathering shaly quartzitic dolomite which produces stunning specimens of a spirifer-type brachiopod identified as Eleutherokomma. Additional Late Devonian brachiopods from the uppermost Lost Burro Beds include Tylothyris cf T. raymondi Haynes, "Camarotoechia" aff. "C" doplicata (Hall), Cleiothyridina cf C. devonica Raymond, and Productella. This photograph, by the way, was originally snapped with a Nikon 35mm camera. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. A view generally southward to mostly the east side of the dirt path through the southern end of Lost Burro Gap. Exposed here is at the exact contact between two Paleozoic Era geological periods. The brownish outcrop at lower left lies at the very top of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation; it is therefore very latest Devonian in geologic age. Behind that point, lies the bluish Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. Geologic age of the precise point where the Lost Burro and Tin Mountain meet is 358.9 million years--transitional Devonian to Mississippian age. Photograph courtesy "Destination4x4". |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. Near the type locality (where a geologic formation was first described in the scientific literature) of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation at the southern end of Lost Burro Gap in Death Valley National Park, California. The view here is west from the junction of Hunter Mountain Road and the primitive jeep track that takes off to Rest Spring Gulch. Roughly the lower one-third of the mountainside is composed of the Lower Silurian to Lower Devonian Hidden Valley Dolomite (which contains locally abundant corals and brachiopods); a little more than a third of the middle portion of the mountain is the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation--a stromatoporoid sponge-rich sequence of dolomites, limestones, sandstones, quartzites and shales that bears common brachiopods, crinoid debris, bryozoans, and an occasional gastropod (famous Orecopia, as a matter of fact). Darker "sliver" of strata to skyline, above the lighter band of Lost Burro Formation, consist of dark blue limestones and shales belonging to the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain limestone--an incredibly fossiliferous Paleozoic Era unit that contains an amazing diversity of solitary and colonial corals, gastropods, trilobites, ostracods, brachiopods, crinoids, bryozoans, and goniatites ammonoids. The photograph, by the way, was originally snapped with a Nikon 35mm camera. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. Geology field trip participants hike to exposures of the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone in the Funeral Mountains, Inyo County, California. The area lies on public lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and is open to hobby collecting of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossils. The Tin Mountain Limestone begins here directly above that narrow inclined reddish-brown band just below the peak; that is the upper part of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation, and thus everything below that point belongs to the Lost Burro Formation. Tin Mountain Limestone forms the very peak here in view and can be followed all the way down the right slope to the hill directly above the head of the field trip participant seen at farthest right of photograph. That narrow band of massive dark blue limestone observed overlying the Tin Mountain Limestone, just below the peak and forming the ridgeline along the right side, is the younger Mississippian Perdido Formation--a narrow "sliver" of which also caps the Tin Mountain limestone at the hill above head of the field trip participant nearest right edge of picture. Image courtesy Dave Smith. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. The light-colored material is a localized Waulsortian Mound in the lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone, Funeral Mountains, Inyo County, California--a specific variety of carbonate mudmound, characterized by abundant crinoid debris and lattice-style bryozoans, that is restricted worldwide to strata of earliest Mississippian geologic age. The locality lies on BLM (Bureau of Land Management)-administered land is therefore open to hobby collecting of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossils. Photograph courtesy James St. John. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. A geologist is examining strata in the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone, Funeral Mountains, Inyo County, California--an area that lies on BLM (Bureau of Land Management)-administered public lands and is therefore open to hobby collecting of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossils. This is in fact famous member t2, which is a medium dark gray limestone that weathers to shades of medium gray; brachiopods are common near the base, while corals become more abundant toward the top, with microfossils--foraminifers (single-celled animals that secreted a geometrically intricate shell) and conodonts (minute tooth-like structures--unrelated to modern jaws or teeth--that served as a unique feeding apparatus in an extinct lamprey-eel-like organism)--associated with both the brachiopods and coelenterates. Relative prevalence of corals in unit t2 is best judged by the fact that all five of the following forms show up in most collections secured from it: Rylstonia, Homalophyllites, Syringopora, Vesiculophyllum, and Caninia. Photograph courtesy James St. John. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Specimens of silicified Syringopora (replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide), an extinct tabulate coral (sometimes called affectionately a "spaghetti coral") from the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone locality near Towne Pass, Inyo County, California; collected on public lands before the paleontologically rich exposures there were assimilated into the borders of Death Valley National Park. Photograph at right, by the way, was originally snapped with a Nikon 35mm camera--then, digitally remastered and eventually edited and processed through photoshop (creating the black background, for one). Image at left taken with a Nikon CoolPix 995 digital camera, then edited and processed through photoshop (adding the black background, for one). |

|

|

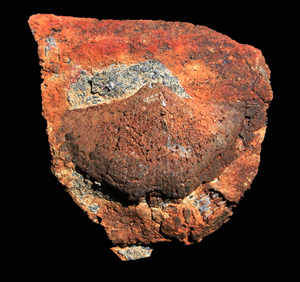

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--A piece of Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone that bears an extinct rugose horn coral; image snapped with a Nikon CoolPix 995 digital camera; later edited and processed through photoshop (creating the black background, for one). Right--an extinct hexacoral called Lithostrotionella from the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. Photographed with a Nikon CoolPix 995 digital camera; later edited and processed through photoshop (creating the black background, for one). Both specimens came from the locality near Towne Pass before the paleontologically rich exposures on public lands there were assimilated into the expanded borders of Death Valley National Park. |

|

|

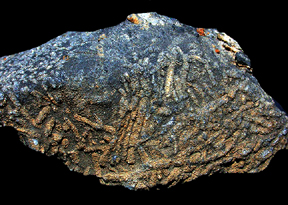

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right. Crinoid columnals from the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone, Funeral Range public lands area, Inyo County, California; the five-sided, star-like structure in the center of each columnal is where the axial canal existed in actual life--the central nerve and circulatory system that extended through the crinoid column; photographed with a Nikon CoolPix 995 digital camera. Right--Silicified crinoid stems (replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide) embedded in a bioclastic matrix from the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone, Funeral Range public lands area, Inyo County, California; photographed with a Nikon CoolPix 995 digital camera. Both images edited and processed through photoshop (creating the black background, for one). |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Silicified crinoid columnals (replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide) embedded in a bioclastic calcium carbonate matrix from the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone, Funeral Range public lands area, Inyo County, California; originally photographed with a Minolta 35mm camera, then digitally remastered and eventually edited and processed with photoshop (adding the black background, for one). Right--A spirifer-type brachiopod from the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. From the Tin Mountain locality near Towne Pass before the paleontologically rich exposures on public lands there were assimilated into the expanded borders of Death Valley National Park; originally photographed with a Minolta 35mm camera, then digitally remastered and eventually edited and processed with photoshop (adding the black background, for one). |

|

|

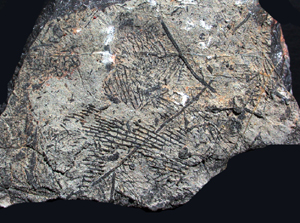

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Lattice-style bryozoans on a chunk of limestone from the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone; from the Funeral Range public lands area, Inyo County, California. Photographed with a Nikon CoolPix 995 digital camera; edited and processed with photoshop (creating the black background, for one). Right--Ostracods (a diminutive bivalved crustacean) from from the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone, Inyo County, California, dissolved free of their calcareous matrix with a solution of diluted acid; exact locality unknown--photograph is courtesy a specific web page. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--"Spaghetti" stromatoporoids called genus Amphipora--an extinct variety of calcareous sponge--observed in the Middle Devonian section of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation at Lost Burro Gap in Death Valley National Park, Inyo County, California. Image at left originally snapped with a Nikon 35mm camera, then digitally remastered--and eventually edited and processed through photoshop (creating the black background, for one); photograph at right taken with a Nikon CoolPix 995 digital camera and later edited and processed through photoshop (creating the black background, for one). |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Two views of the same extinct stromatoporoid calcareous sponge observed in the Middle Devonian section of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation at Lost Burro Gap in Death Valley National Park, Inyo County, California. Image at left is a "head-on" perspective of the top of the two conical structures seen in photograph at right. Both photographs taken with a Nikon CoolPix 995 digital camera and eventually edited and processed with photoshop (creating the black background, for one). |

|

|

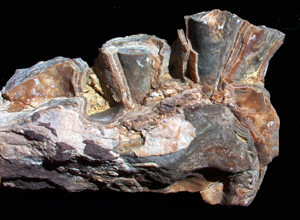

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--A spirifer brachiopod called genus Eleutherokomma observed in the Upper Devonian section of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation at Lost Burro Gap in Death Valley National Park, Into County, California; originally photographed with a Nixon 35mm camera, then digitally remastered and eventually edited and processed through photoshop. Right--An extinct tabulate coral called Halysites observed in the Lower Silurian section of the Lower Silurian to Lower Devonian Hidden Valley Dolomite in the vicinity of Lost Burro Gap in Death Valley National Park, Inyo County, California; originally photographed with a Nikon 35mm camera, then digitally remastered--and eventually edited and processed with photoshop (creating the black background, for one). |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures--and scientific names for the specimens numbered. Left and right--Conodonts (greatly magnified) that technicians--with permission from the National Park Service--dissolved out of the Lower Silurian section of the Lower Silurian to Lower Devonian Hidden Valley Dolomite at its type locality in Hidden Valley, just south of Lost Burro Gap in Death Valley National Park, Inyo County, California. Conodonts are minute structures--unrelated to modern jaws and teeth--that served as a unique feeding apparatus in an extinct lamprey eel-like organism. Photographs courtesy a specific scientific publication. |

|