|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Explorers of Miocene paleontology at Fossil Valley excavate paper shales in the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Great Basin Desert, Nevada; the classically fossiliferous, extraordinarily thin-bedded detrital deposits (preserved in"paper thin" layers) not only produce innumerable beautifully preserved insects, but also many exquisitely detailed leaves (both evergreen and deciduous varieties), seeds (from pine, fir, spruce, Douglas fir, and maple), conifer needles, conifer foliage (from giant sequoia and cypress), pollens, bird feathers, and fishes some 14.5 million years old. Mudstones and diatomaceous shales frequently yield prodigious quantities of wonderfully preserved diatoms--microscopic single-celled photosynthesizing algae that constructed fascinating "shells" composed of silica, technically termed a frustule. Coarser-grained sedimentary beds in Fossil Valley bear bonanza strata loaded with freshwater gastropods, pelecypods, and ostracods (a minute bivalved crustacean). Carbonate sequences often contain nicely preserved blue-green algal stromatolite developments--concentrically laminated dome-configured structures precipitated by cyanobacterial activity. Near-shore sandstones and siltstones mixed with air-fall volcanic constituents provide abundant petrified woods and numerous vertebrate specimens--mammals, amphibians, and reptiles between 16 and 10 million years old. Image taken before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--An undescribed hoverfly (10mm long in actual size). Also called flower flies, or even syrphid flies; belongs to the insect family Syrphidae--these guys really like to pollinate, often considered the second-most important group of pollinators after wild bees. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photograph by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized fossil collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

Journey through cyberspace to Fossil Valley, a world-famous desert district situated in Nevada's Great Basin geomorphic province that contains the most complete, diverse, terrestrial (land-laid) fossil record of Miocene life yet discovered in North America--and perhaps the world, as a matter of fact--a genuinely spectacular paleontological place that produces from what earth scientists call the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation an astounding association of well-preserved fossil material some 16 to 10 million years old, including: insects (preserved in exquisite detail along the bedding planes of very thinly stratified sedimentary rocks commonly called "paper shales"); plants (leaves, seeds, flowering structures, conifer needles and foliage, diatoms--a microscopic single-celled photosynthesizing algae that constructed silica "shells"/frustules--pollens, and petrified woods); stromatolitic, cyanobacterial blue-green algal developments; mollusks (gastropods and pelecypods); ostracods (a bilvalve crustacean); mammals; birds; fish; amphibians; turtles; and arachnids (spiders). Indeed, it's quite likely that no other place on the planet provides a better opportunity to study such a rich, essentially complete paleo-community of terrestrial Miocene plants and animals. Here, you'll find a synthesis of information pertaining to Fossil Valley, Nevada--including a detailed field trip text; complete lists of fossil species technicians have secured from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation; photographs of representative fossils; and on-site images, as well. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

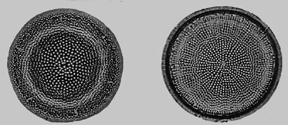

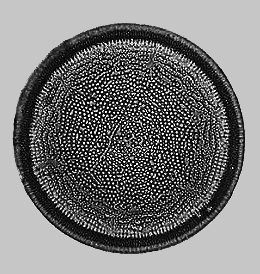

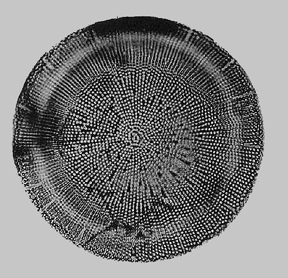

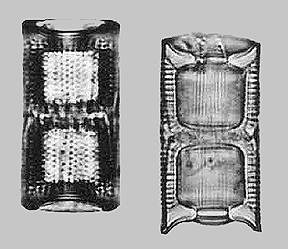

It's often called Nevada's paleontologic crown jewel of the Neogene (on the geologic time scale, roughly 23 to 2.58 years ago). A place that yields North America's single best fossil representation of terrestrial, land-laid Miocene plants and animals from a time interval of approximately 16.4 to 10.5 million years ago; too, arguably no other land-deposited Miocene geologic area on earth rivals its combined organismal diversity and preservational preeminence. That would of course be Fossil Valley, situated in the Great Basin Desert geomorphic province. Its exalted reputation among students of paleontology lies in its unusually complete record of later Cenozoic Era life kept in an overall exceptional state of preservation for roughly 16 million years in what geologists, stratigraphers, and paleontologists alike call the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation. Documented organic specimens discovered from Esmeralda Formation exposures in Fossil Valley, Nevada, include a practically unprecedented, unparalleled, multiplicity of excellently preserved forms that contribute to an essentially complete paleoenvironmental biota. Among the numbered: insects (preserved in exquisite detail along the bedding planes of very thinly stratified sedimentary rocks commonly called "paper shales"); arachnids (spiders); plants (leaves, seeds, flowering structures, pollens, conifer needles and foliage, diatoms--a microscopic single-celled photosynthesizing algae--and petrified woods); blue-green algal stromatolite developments--concentrically laminated dome-configured structures precipitated by cyanobacterial activity; mollusks (gastropods and pelecypods); ostracods (a minute bilvalve crustacean); fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Within Fossil Valley, the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation is roughly 600 meters thick (1,970 feet) and ranges in geologic age from 16.4 to approximately 10 million years old. Twelve major fossil horizons between roughly 16.4 to 10.5 million years ancient lie stacked atop one another in mostly conformable, successive stratigraphic relations--which is to say that deposition of the Esmeralda here was pretty much continuous, with few significant interruptions in sedimentary accumulation. For organized, nomenclatural ease of stratigraphic descriptions, geologists have separated Fossil Valley's Esmeralda Formation into seven subunits, or members, which reflect distinct depositional lithologies that can be mapped across wide areas of rock outcropping. Initiation of the Miocene Fossil Valley lake basin begins around 17 million years ago with right-lateral fault displacement associated with extensional geophysical stresses that accompanied incipient formation of the Great Basin geomorphic province. Oldest Miocene rocks in Fossil Valley are paleontologically barren volcanic andesites, overlain by a dacite breccia (also devoid of fossil material) dated at around 17 million years old. Member One of the Esmeralda Formation interfingers with and overlies the breccia interval, consisting of some 100 to 150 meters (320 to 490 feet) of, in ascending order (oldest to youngest): dark-colored mudstone and shale; light-colored siltstone, sandstone, and calcareous sandstone; and blue-gray volcanic-clastic sandstone. Member One's mudstones and siltstones preserve the earliest fossil leaves in the Esmeralda Fossil Valley sequence, approximately 16.4 million years ancient, in addition to several geologically younger ostracod coquinas composed almost entirely of the minute (typically, around 1mm long) bivalve crustacean sometimes colloquially called a "seed shrimp" (though the ostracod is not directly related to a shrimp). Bountiful freshwater mollusks (gastropods and pelecypods) occur locally in the calcareous sandstone facies, while abundant silicified petrified wood (replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide) plus mammalian teeth and post cranial skeletal elements often commonly weather free from the coarser sandstone horizons; reptile and amphibian bones also occasionally occur in the same interval. The mollusks, ostracods, petrified woods, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals have been dated to roughly 15.4 to 15.1 million years old. Above the primarily clastic Member One lie additional detrital deposits assigned to the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation--the fabulous, world famous "paper shales" of Member Two--roughly 55 meters (180 feet) of laminated, exceedingly thin bedded brown to dark-gray siliceous shales that bear beautifully preserved insects, arachnids, leaves, winged conifer seeds, conifer needles and foliage, flowering structures, pollens, bird feathers, and complete fish skeletons some 14.5 million years old. Lying directly above the paper shales of Member Two is Member Three's 90 meters (295 feet) of mostly white to buff-colored mudstone and shales, all of which represent deposition in the center of the Fossil Valley basin. Fossil plants, fish scales, and ostracods occur in several of the sedimentary layers. Next youngest sequence is Member Four, which just happens to be the most widespread unit exposed throughout Fossil Valley's Esmeralda Formation stratigraphic complex. Its extensive regional area of outcropping, as a matter of fact, helps paleogeographers estimate a maximum size for the ancestral Fossil Valley basin--the conclusion: eight kilometers wide (five miles) by 16 km long (10 miles). Member Four consists of approximately 45 meters (147 feet) of white to cream-colored diatomaceous shales, diatomaceous mudstones, and blue vitric volcanic ash layers. The diatomaceous sediments are composed of myriads of diatoms--microscopic single-celled photosynthesizing algae that secreted an opaline silica "shell," technically called a frustule. Separating Member Four from the younger Member Five is a minor erosional unconformity, marked by a prominent soil profile that developed on Member Four's predominantly diatomaceous deposits before additional sedimentary accumulations commenced. Above the buried soil profile lies around 140 meters (460 feet) of buff to brown and gray-colored siltstones, sandstones, and a rather thin-bedded pebble conglomerate. An important early Clarendonian Stage mammalian vertebrate fossil locality some 13 million years old occurs just above the base of Member Five's buried soil horizon; elsewhere, the unit produces isolated fish bones and occasional mollusks (gastropods and pelecypods). Fully conformable above the bone-bearing Member Five, without erosional break in the continuous regimen of fluviatile sedimentary deposition, is the gradationally younger Member Six--about 40 meters (131 feet) of blue volcaniclastic sandstone (contains weathered volcanic constituents) with subordinate layers of interbedded buff to brown and blue-gray sandstone. Member Six yields significant concentrations of several species of Clarendonian mammals in strata approximately 12 million years old. Youngest geologic unit in Fossil Valley's Esmeralda Formation is Member Seven, whose base is marked by a persistent 2.5 meter-thick layer (8 feet) of white biotite volcanic tuff dated through radiometric measurements at 10.7 million years old. Above that horizon rests about 90 meters (295 feet) of volcaniclastic siltstones and sandstone, with lesser admixtures of volcanic ash that as a mappable lithologic group undergo a persistently consistent color change throughout Fossil Valley. Approximately the lower 50 meters is white to light gray-colored siltstone, followed by 20 meters of pale green siltstone and then 20 meters of pale pink sandstone. Many classic late Clarendonian Stage vertebrate fossil localities around 10.5 million years old occur in the upper half of Member Seven. Among Fossil Valley's numerous significant paleobiological representatives, probably its exceptionally well preserved insects (and occasional arachnids--spiders) attract the most consistent scientific and popular attention. Worldwide, paleoentomologically productive deposits that yield so many readily identifiable, exquisitely detailed fossil specimens remain fantastically rare occurrences, indeed. Fossil Valley's world-famous "bugs" occur of course in the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, but remain restricted to the so-called "paper shale" deposits of Member Two--layers of shale so thinly bedded that each individual stratrum is classically no thicker than a proverbial sheet of paper--dated through radiometric techniques at around 14.5 million years old. Petrographic analysis of the insect-bearing paper shales proved that the fossiliferous detrital deposits consist almost entirely of finely eroded grains of cristobalite, a high temperature polymorph of silica--meaning that it bears that same chemical structure as silica (SiO2), but in a different molecular crystal arrangement. And what a veritable treasure trove of supremely well preserved freshwater arthropodal fossils the paper shales contain. A representative sampling of insect specimens includes: gall gnats, fungus gnats, midges, jumping plant lice, fulgorid bugs, true bugs, damsel bugs, beetles, metallic wood borers, mayflies, march flies, moths, dragonflies, crickets, termites, aphids, butterflies, mosquitoes, fruit flies (hoverflies), Crane flies, leaf-miner flies, bibionid flies, bees, yellow jackets, ichneumon wasps, lacewings, leaf hoppers, and ants. Dipteran flies and gnats comprise approximately fifty percent of the Esmeralda Formation's paleoentomological fauna, while members of the Hymenoptera (exemplified by ants and ichneumon wasps) make up around twenty-five percent; the remaining insectan content percentage is composed of, primarily: Hemiptera (lacewings); Coloeptera (beetles); Ephemeroptera (mayflies); Odonta (dragonflies); and Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies). A general "rule of thumb," as it were, is that Fossil Valley produces a predominantly diminutive fossil insect assemblage; an observation that naturally leads one to the tempting working hypothesis that specimens recovered from the paper shales accumulated in rather deep, anoxic waters (severely oxygen-depleted), far removed from near-shore areas where turbulence and greater decay-inducing oxygen content would tend to obliterate delicate arthropodal tissues of larger insects recently cast to the waters. On the other hand, one must note that numerous examples of Fossil Valley Diptera (flies and gnats, in particular) would appear to have been flung forcefully to a fine-grained surface, preserved as they are in quasi-smashed, contorted death positions--suggesting that at least a percentage of the unfortunate arthropods met their demise when blown to the sticky vast mudflats of a moist playa floor. Another taphonomic explanation for Esmeralda Formation freshwater arthropod preservations involves the influence of mucus. Call it the "paleo-spit" idea, if you will. What researchers perspicaciously observed was that elsewhere in the world many exceptionally preserved fossil insects often tend to occur in the presence of microbial films produced by diatoms (Colorado's famed Florissant fossil insect association, for example). That is to say, investigators concluded that diatoms, during periods of overstimulated bloom, "exuded" a sticky mucus-like substance which helped slow the invariably rapid decomposition of insects adhering to it, until the arthropods could be buried by a protective layer of lake bottom mud, or volcanic ash. But of course, many of Fossil Valley's insects required plants to survive. Paleobotanically important leaf, seed, and conifer foliage impressions from Fossil Valley come from two primary horizons separated by several million of years of geologic time. The older fossiliferous layer is preserved in mudstones and siltstones approximately 16.4 million years old, while the younger localities lie within the world-famous paper shales dated at around 14.5 million years ancient. Plant species recovered from the older 16.4 million year-old stratigraphic interval resemble in great part vegetation varieties that contribute to the lush deciduous forests of the eastern United States. Estimated precipitation during that particular period of middle Miocene time was probably as high as 100 centimeters per year (39 inches)--with reliable patterns of summer rainfall, as well--a decidedly mesic paleoenvironment, well-watered, that encouraged the proliferation of a healthy broad-leafed canopy. Representative floristic material secured from the older plant-bearing horizon includes--common specimens of alder, birch, walnut, persimmon, Eugenia, Kentucky coffeetree, Malus (related to the apple), a member of the genus Prunus (which includes plums, cherries, peaches, nectarines, apricots and almonds), Photinia (yet another species that some call the Christmas berry), black walnut, poplars, hawthorn, Chinese scholar tree, barberry, gooseberry, whitebeam, tassel bush, lobed red oak, stone oak, an extinct water oak, elm, zelkova, sycamore, and maple--in addition to such conifers as fir, spruce, and hemlock; average year-round temperatures likely never exceeded 10 degrees Celsius. (50 F). At around 15 million years ago, ancestral western North America, in general, began to experience a dramatic shift in climatic conditions. By 14.5 million years ago, for example, average year-round temperatures had dropped approximately three degrees Celsius to 7 degrees C (44 degrees F), and summer rainfall patterns had all but dried up; annual precipitation probably fell from the previous highs of 100 centimeters (39 inches) to 75 centimeters (29) inches per year. This rather rapid (geologically speaking) alteration of paleoenvironmental patterns pretty much eliminated from Fossil Valley all of its once-dominant broad-leafed deciduous plant life. In the younger 14.5 million year-old fossil flora above the older zone, no deciduous hardwoods of eastern alliance that characterize the 16.4 million year-old plant bed have been recovered. Replacing the many Esmeralda exotic hardwoods that now inhabit eastern United States forests was a botanic biota now represented by many evergreen dicotelydons and conifers. Commonly observed fossil plant remains identified from the younger Esmeralda Formation paper shales include--giant sequoia (foliage), Alaskan cedar, hemlock, spruce, fir, false cypress, larch, pinyon pine, juniper, manzanita, black cottonwood, mountain cottonwood, quaking aspen, Himalayan aspen, American aspen, willows, evergreen live oaks, oceanspray, mockorange, serviceberry, Catalina ironwood, mountain mahogany, toyon (sometimes called Christmas berry), buckthorn, squaw apple, silverberry, coast silk-tassel, oregon grape, elderberry, soapberry, pepper tree, hickory, mountain ash, locust, curl-leaf sumac, and madron. In many floristic respects, the younger Esmeralda Formation plants begin to resemble in a general sense the associations of shrubs and trees now found growing along the western slopes of California's Sierra Nevada. In addition to the bountiful, exquisitely detailed leaves, seeds, conifer foliage, and flowering structures preserved along the natural bedding planes of mudstones, siltstones, and thinly bedded shales in Esmeralda Formation members One and Two, rather common to abundant petrified woods can also be found concentrated in localized, so-called mini-petrified forests throughout the coarser-grained fluviatile (river-deposited) sedimentary sections of Esmeralda Member One. Much of the woody material is nicely silicified--that is, replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide--although not even a smidgen of it has been definitively identified, let alone formally described in the scientific paleobotanical literature. Casual inspection, though, leads not a few investigators to believe that much of the petrified would could well derive from giant sequoia trunks. Thriving in the lakes that once lapped the now mineralized trees is a fascinating group of minute organisms that provides students of the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation with one of the more prolific paleontologic occurrences yet known from Fossil Valley Basin--the diatom, a microscopic photosynthesizing single-celled phytoplanktonic algae, that secretes a "shell" composed of opaline silica (the mineral silicon dioxide)--a diatom home technically termed a frustule. Though micropaleontologists often recognize their fossil remains under moderately high powers of magnification as isolated cells of varying intricate shapes and sizes, diatoms were still quite capable of forming chains or links, mimicking a multicellular organism. They first appear in the geologic record during the early Jurassic, approximately 185 million years ago, but molecular clock calculations (genetic DNA analyses) and sedimentary evidence point to an earlier established presence in the Triassic Period. Since roughly 100 million years ago, beginning in the Cretaceous Period (age of dinosaurs, or course), diatoms have pretty much owned the so-called silica cycle, flourishing in both marine and freshwater habitats while contributing throughout the late Cretaceous Period and succeeding Cenozoic Era myriads of their frustules to the ever-accumulating fossil record; indeed, during Miocene times throughout ancestral Nevada diatoms occasionally formed impressive deposits of commercially exploitable diatomite, a sedimentary rock type composed almost entirely of diatoms. At Fossil Valley, within the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, diatoms accumulated in several punctuated, successively stratified geologic horizons distributed between irregularly spaced barren layers denoting dramatic diatom kill zones precipitated by periodic air-fall volcanic ash, which paradoxically provided plentiful dissolved silica for additional diatom "colonies" to become established--until, that is, yet another pyroclastic episode devastated diatom reproduction dynamics. Fossil Valley has provided micropaleontology investigators with some 109 diatom species. Characteristic Esmeralda Formation examples include--Anomoeoneis lanceolata, Anomoeoneis nyensis, Anomoeoneis turgida, Fragilaria crassa, Stauroneis debilis, Surirella spicula, Cestodiscus cedarensis, Cestodiscus fasciculatus, Cestrodiscus stellatus, Pinnularia esmeraldensis, and Tetracyclus radiatus. Diatom specialists note that the presence of a number of diagnostic pelagic and littoral forms demonstrates that Fossil Valley Lake's deeper waters were at times eutrophic (biologically productive), low in salinity (probably between 0 and 5 parts per thousand), clean, and generally alkaline. Still and all, diminishing frequencies of Tetracyclus (a cold water diatom) in successively younger stratigraphic intervals certainly suggests an overall shallowing of Fossil Valley Lake over geologic time. Most diatom assemblages from the Esmeralda Formation yield species whose living members now dominant saline and brackish lakes, paleontologic evidence which likely explains the presence of a normally marine genus in the freshwater Fossil Valley collections--Cestodiscus. A minor introduction of alkaline-loving members of the diatom genera Pinnularia indicates that periodically, at least, Fossil Valley Lake's pH levels could have gone greater than 7.0. For the Esmeralda Formation stratigraphic section containing Coscinodiscus miocaenicus and Coscinodiscus grobunovii diatoms, a geologic age of 15 to 12 million years is suggested. Also living throughout the Fossil Valley Lake hydrologic system were untold numbers of freshwater mollusks and ostracods (a tiny bivalve crustacean), whose often well preserved remains now lie encased in Esmeralda Formation strata approximately 15 to 14 million years old. Among Fossil Valley's prolific freshwater molluscan assemblage, some 34 species of gastropods and pelecypods have been identified from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation--four clams and 30 snails, all told. Most occur in the calcareous sandstone and silty limestone layers of Member One, often developing widespread coquinoid associations where the matrix is composed almost entirely of whole and broken shells. The most abundant varieties recovered include four species of rather diminutive pelecypods distributed within the genera Pisidium (two species) and Sphaerium (two species)--often referred to colloquially by malacologists as "fingernail clams"--in addition to the following gastropods: Vorticifex (six species); Valvata (three species); Viviparus (two species); and Goniobasis (three species). The fossil freshwater mollusks inform paleolimnologists and paleoecologists much about ancestral Fossil Valley's middle Miocene lacustrine and fluviatile conditions. For example, Vorticifex sp. belongs to the freshwater gastropod family Planorbidae, the planorbids (technically categorized as an "aquatic pulmonate gastropod mollusk" that breaths air), whose living representatives often find their way into aquariums under the common name "ramshorn snails" (admittedly, of course, not all gastropods advertised as aquarium-ready "ramshorns" are actually planorbids). During Esmeralda times some 15 to 14 million years ago, Vorticifex snails likely lived in vegetation-rich waters no deeper than 15 feet, though in actual fact their extant representatives remain manifestly happier at depths of about six feet. Another gastropodal dominant is Viviparus sp. (family Viviparidae), which interestingly enough uses a gill to respire. It's a relatively large, exclusively freshwater mollusk (grows up to two and a half inches long) that tolerates a wide range of habitats: ponds, rivers, streams, marshes, backwaters, and permanent bodies of water of varying depths. In North America, recent Viviparus species remain restricted to areas east of the Rocky Mountains at latitudes below 52 degrees. Dispersal in an ecosystem is likely achieved by active molluscan movement through water channels, with rafting a theoretical possibility that's never actually been witnessed. Diet is exclusively herbivorous; the snails feed on vegetation growing in the silty and sandy bottoms. An additional observation is that Viviparus gives live birth to its young, although all youngsters hatch inside the female snail's body and emerge only when environmental conditions are optimal (technically, a process called ovovivipary). A third freshwater gastropod common to Fossil Valley's Esmeralda Formation exposures is Goniobasis sp., which is the extinct molluscan equivalent of the living genus Pleurocera (family Pleuroceridae) now native to eastern North America; a related genus called Juga resides in the US west. It's often mistaken for a Turritella marine gastropod because of its characteristic high-spired morphological configuration. The Eocene Green River Formation, for example, produces plentiful silicified layers of Goniobasis snails, usually marketed under the name "turritella agate." Goniobasis was a gill breather that could generally tolerate varying degrees of salinity and even adverse turbulent waters. The fourth Fossil Valley Esmeralda Formation gastropod dominant is Valvata sp. (family Valvatidae)--an operculum-bearing snail that possesses a gill attached only by the base so that it forms a structure like a feather outside the shell when fully extended. Modern Valvata species almost exclusively inhabit large, permanent bodies of water such as rivers and lakes. And they're also almost universally intolerant of waters with a pH level below 7.0; hence, the presence of Valvata indicates with invariable high probability an alkaline lake chemistry. Fossil Valley's freshwater pelecypodal preservations consist of two forms, both members of the family Sphaeriidae--Pisidium and Sphaerium. Living members of the Shaeriidae inhabit a wide range of conditions, from shallow to deep waters, but generally prefer depths less than 6 feet. Although sphaeriids like slightly alkaline environments, Sphaerium has nevertheless been reported from waters with a borderline acidic pH of 6.0. Too, they'll tolerate just about any kind of substrate--except bottom areas composed of rocks or clay; that they will not abide. The ostracods from Fossil Valley Esmeralda exposures are numerous, indeed. Often colloquially called "seed shrimps," ostracods are minute (typically around 1 millimeter long, but often as small as 0.2mm) bivalve arthropod crustaceans, not directly related to shrimps, that today inhabit both marine and freshwater environments; they first appear in the geologic record during the early Ordovician Period, approximately 485 million years ago. Scientific investigators usually consider them accurate, sensitive indicators of water chemistry, depth, and temperature. They also provide earth scientists with a superior utility to help calculate the relative geologic ages of rock formations in which ostracods occur. In Fossil Valley Lake, they were obviously gregarious organisms, multiplying with efficient overpopulating explosiveness when the proper environment conditions arose--commonly contributing to the sedimentary accumulations impressive zoned coquinoid associations. Within the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation some 35 ostracod species have been described. Typical forms include Pactolocypris cancellatus, P. pactolensis, P. biprojectus, Heterocypris blairensis, Kassinina microreticulata, Advenocypris concinnus, Procyprois gracilis, Hemicyprinotus ionensis, Eucypris fingerrockensis, Cypricercus mineralensis, and Dongyingia lariversi, Dogelinella coaldalensis, Disopontocypris hendersoni, and Cypridopsella esmeraldensis--an informative selection of fossil crustacean material that suggests that Fossil Valley Lake, during periods of ostracod accumulations, probably experienced pronounced pulsations of saline-dominated, brackish water paleolimnological fluctuations. Not only are innumerable middle Miocene plants and invertebrate animals preserved at Fossil Valley Basin, but the backboned kinds get in the act in a big way, as well. Vertebrate fossils recovered from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation at Fossil Valley include fish, amphibians, a reptile, birds, and mammals. The fossil fish occur as isolated bones, scales, and often common complete skeletons in the world-famous paper shale horizon of Esmeralda Formation member Two, approximately 14.5 million years old. Two major types predominate: an undescribed salmonid, which is related to salmon, char, and trout--probably its closest living relative is the Dolly Varden trout--and a Chub called scientifically Gila sp., a member of the Cyprinidae family (minnows, chubs, European daces, carps, and chars are other examples). Additionally, some years ago a paleontologically fortunate member of the United States Geological Survey found a pharyngeal arch that resembles the hardhead, a member of the Cyprinidae now native to California; that specimen has never been formally described in the scientific literature, though. Amphibian skeletal elements identified are indistinguishable from the living Couche's Spadefoot toad native to parts of southeastern Colorado, southern Oklahoma, western Texas, New Mexico, southern Arizona, southeastern California, northern Mexico, and the Baja peninsula; its scientific name is Scaphiopus alexanderi, named for famed fossil hunter and naturalist Annie Alexander who collected it from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation. One undescribed alligator snapping turtle was mentioned among Esmeralda finds in the late 1950s. Numerous bird feathers have been secured from the paper shale deposits, as well--among them, identifiable specimens belonging to a golden eagle, a burrowing owl, a turkey vulture, and a pinyon jay. The middle Miocene mammals from Fossil Valley are many, and varied. They typically occur in two major Esmeralda Formation horizons--an older vertebrate accumulation specific to the Barstovian Stage of the Miocene Epoch that dates from approximately 15.4 to 15.1 million years ago--and then a younger bone interval from the Clarendonian Stage, somewhere around 13.5 to 10.5 million years old. Both faunas supply vertebrate paleontologists with some of the most iconic Miocene mammals that ever walked the earth. Older of the two vertebrate associations occurs in overbank fluviatile deposits associated with Member One of the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation. Here can be found a paleontologically satisfying representative cross-section of land life that roamed ancestral middle Miocene Fossil Valley a little over 15 million years ago. Among the many significant mammals, for example, was a group of interesting insect-eaters--a hedgehog-like critter; a shrew; a mole; a curious extinct ground-dwelling insectivore (Arctoryctes); and a bat. Diminutive rodents and lagomorphs (hares-rabbits-pikas) also resided at Fossil Valley during Barstovian Stage times: the faunal listing includes: two kinds of squirrels; two extinct squirrel-like animals; two beavers; a kangaroo rat; and an extinct rabbit-like creature. Carvivores were nicely represented, as well. Examples of meat-eaters from the older Esmeralda Formation horizon include: an extinct bear-dog (Tamarctus); an extinct hyena-like dog (Aelurodon); a fox; a ring-tailed cat; and an unspecified member of the Mustelidae, which includes otters, badgers, weasels, martens, ferrets, minks and wolverines. Larger Barstovian-age Fossil Valley herbivores attempting to evade the carnivores amounted to a diverse lot, indeed. Obligate vegetation munchers described from the oldest middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation section include: an extinct elephant-like gomphothere proboscidean; three different species of extinct three-toed horses (one Hypohyppus and two Merychippus); a rhinoceros; two camels; an extinct three-horned ruminant (a Palaeomerycid); and two extinct pronghorns (Merycodus). The geologically younger Fossil Valley vertebrates occur in Esmeralda strata deposited during the Clarendonian Stage of the middle Miocene, a mammal-producing section dated at roughly 13.0 to 10.5 million years old. That's where important bone-bearing beds lie positioned through many hundreds of feet of Esmeralda Formation members Five, Six and Seven. And the faunal list is quite inclusive: an extinct shrew-like insectivore (Limnoecus); two kinds of squirrels; four members of the Heteromyidae rodent family--three extinct pocket mice (Perognathus) and an extinct critter closely related to the pocket mouse (Cupidinimus); a giant kangaroo rat; a beaver; a deer mouse; a rabbit; a bear-dog (Tamarctus); a fox; two species of a bone-crushing hyena-like dog (Aelurodon); a member of Mustelidae family, which includes badgers, otters, weasels, martens, ferrets, minks, and wolverines; an extinct cat (Psudaelurus)--an ancestor of today's felines and pantherines as well as the extinct saber-tooths; an extinct felid carnivore (Sansanosmilus) commonly called a false saber tooth cat; two kinds of elephant-like gomphothere proboscideans; five types of extinct horses--the last browsing horse in North America (three-toed Megahippus), two species of three-toed grazing horses (Neohipparion and Hypohippus), and two species of the single-toed grazer Pliohippus; a rhinoceros; three types of camels; and an extinct pronghorn (Mercycodus). Today, while visiting Nevada's Great Basin Desert within the midst of such an unimaginably vast expanse of arid, ecologically austere territory dotted with creosote, shadscale, and additional botanically specialized compact spinescent types adapted to prolonged periods of scant precipitation--less than five inches per year, on average--it is perhaps difficult to imagine Fossil Valley as an extensive verdant lake basin teaming with luxuriant trees and shrubs and grasses and abundant animal life But the eroding rocks of the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation prove the case: This is a land dominated by the good dust of deep time, by the weathered sedimentary particles from a geologically hardened hydrologic system that disappear into the infinite distance as an incessant desiccated wind whips across stone outcroppings of a 17 to 10 million year-old lake--each gone grain gradually releasing to view the paleontologic wonders for which Fossil Valley is appreciated worldwide--a unique, complete, paleo-biota of middle Miocene organisms retained in an exceptional state of preservation: the leaves, the conifer winged seeds and needles and foliage, the petrified woods, the pollens, the diatoms, the stromatolites, the gastropods, the pelecypods, the ostracods, the fish, the amphibians, the turtles, the birds, the mammals--and the insects, whose delicate winged varieties often seem so life-like that they appear ready to fly away from the water-born sedimentary layers upon which they've lived for fourteen and a half million years. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Explorers of the Cenozoic Era excavate the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation for fossil insects, leaves, and fish. Photograph taken before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Right--Parked in the famous petrified forest amphitheater, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Exposed here are abundant petrified woods, weathering out of the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation. Photograph taken before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Here's renowned "Snail Cliff" in Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. That "cliff" exposure is composed of layer upon layer of stratified beds that produce innumerable well-preserved freshwater gastropods in the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation. Photograph taken by author before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Right--Parked in Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Hill in background is composed of the fossiliferous middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, which here yields plentiful, extraordinarily well preserved fossil insects some 14.5 million years old. Photograph taken by author before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. And now a brief diversion--something a little different. Click Here for some music. Yes, indeed. It's an acoustic version of that old campfire standard "Mama Don't Allow." My father and I recorded it several years ago with a portable stereo cassette tape machine while camped in Fossil Valley--at that very spot where the jeep is parked. That's dad on vocals and playing the 1976 Martin D-35 guitar; I'm playing the lead, plus solos, on a 1952 Martin 0-18. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--A panorama that includes classic fossil mammal-bearing beds in the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation (reddish-brown and whitish sedimentary material in distance), Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Photograph taken by author before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Right--Traveling through Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Fossil mammal-bearing beds of the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation in low foothills directly ahead. Photograph taken by author before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--A seeker of Miocene paleontology at Fossil Valley excavates paper shales in the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. The classically fossiliferous paper shales produce innumerable beautifully preserved insects, leaves, and fishes some 14.5 million years old. Photograph taken before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--A dedicated barbecuer braves fierce freezing weather at Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada, to cook up some tasty meats. Photograph taken before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Left--Here's the turnoff to Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada, which contains the most diverse, complete, terrestrial (land-laid) record of Miocene plant and animal life yet recognized from North America--and perhaps the world, as well, as a matter of fact. The fossil material in Fossil Valley (a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten) occurs in the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation. A Google Earth street car photograph I cropped and processed through photoshop. At right is a campsite in Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Note the AMC CJ7 jeep and Open Road camper. Photograph taken by author before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--An undescribed fly (in actual size, 5mm long); belongs to the insect Order Diptera. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--A Crane fly; belongs to the insect family Tipulidae. Called scientifically Tipula nevadensis. In actual size: body 15.8mm long; largest wing--18.3mm x 4.0mm; from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photograph by the long-time doyen of Nevada Cenozoic Era paleotobotany--the late paleobotanist Howard E. Schorn (former Collections Manager of fossil plants at the University California Museum of Paleontology). Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--An undescribed fly (in actual size, 8mm long); belongs to the insect Order Diptera. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--An undescribed ant, with a wing still attached (in actual size, 5mm long); belongs to the insect Family Formicidae. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

a.jpg) |

|

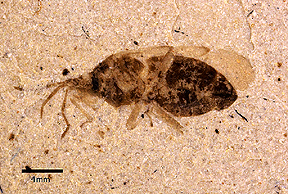

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--An undescribed ant from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Actual size--5mm long. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Right--An undescribed true plant bug (not all insects are technically classified as"bugs," of course). From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographed by the long-time doyen of Nevada Cenozoic Era paleobotany, the late paleobotanist Howard E. Schorn (former Collections Manager of fossil plants at the University California Museum of Paleontology. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right: Two undescribed bibionid flies (fungus gnat and March fly, respectively) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of each image. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Both photographs taken by an individual named Iyawna Hazzard, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified both images with photoshop. Note that identification of fossils and their assignment to a geologic rock formation are my responsibility, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the University California Museum of Paleontology. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right: Two undescribed midge insects from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of each image. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Both photographs taken by an individual named Iyawna Hazzard, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified both images with photoshop. Note that identification of fossils and their assignment to a geologic rock formation are my responsibility, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the University California Museum of Paleontology. |

|

|

|

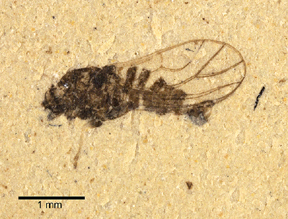

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: An undescribed ant from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower right of image. Note that all four of the ant's wings have been preserved. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Photograph taken by an individual named Iyawna Hazzard, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Right--An undescribed true plant bug (not all insects are technically classified as "bugs," of course) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Photograph taken by an individual named Marwa W. El-Faramawi, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Note that identification of fossils and their assignment to a geologic rock formation are my responsibility, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the University California Museum of Paleontology. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: An undescribed gnat from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Photograph taken by an individual named Iyawna Hazzard, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Right--An undescribed fly from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Photograph taken by an individual named Dave Strauss, courtesy Copyright © University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Note that identification of fossils and their assignment to a geologic rock formation are my responsibility, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the University California Museum of Paleontology. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: An undescribed midge from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Note that the midge's eyes are staring directly back at you. Photograph taken by an individual named Marwa W. El-Faramawi, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Right--An undescribed bibionid fly (fungus gnat) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Photograph taken by an individual named Marwa W. El-Faramawi, courtesy Copyright © University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Note that identification of fossils and their assignment to a geologic rock formation are my responsibility, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the University California Museum of Paleontology. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right: Two undescribed jumping plant lice from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of each image. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Top photograph taken by an individual named Iyawnna Hazzard, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. Bottom image by Marwa W. El-Faramaw, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified both images with with photoshop. Note that identification of fossils and their assignment to a geologic rock formation are my responsibility, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the University California Museum of Paleontology. |

|

|

|

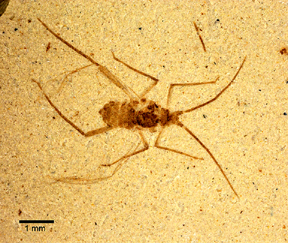

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: An undescribed ant from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Two millimeter scale at upper left of image. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Photograph taken by an individual named Marwa W. El-Faramawi, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Right--An undescribed fly from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Photograph taken by an individual named Iyawnna Hazzard , courtesy Copyright © University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Note that identification of fossils and their assignment to a geologic rock formation are my responsibility, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the University California Museum of Paleontology. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: An undescribed true plant bug (not every insect is technically classified as a "bug," of course) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Photograph taken by an individual named Marwa W. El-Faramawi, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Right--An undescribed damsel bug from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Photograph taken by an individual named Marwa W. El-Faramawi, courtesy Copyright © University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Note that identification of fossils and their assignment to a geologic rock formation are my responsibility, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the University California Museum of Paleontology. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: An undescribed beetle from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Photograph taken by an individual named Iyawnna Hazzard, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Right--An undescribed midge from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Photograph taken by an individual named Iyawnna Hazzard, courtesy Copyright © University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Note that identification of fossils and their assignment to a geologic rock formation are my responsibility, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the University California Museum of Paleontology. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right: Part and counterpart of an undescribed leaf-miner fly from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Millimeter scale at lower left of image. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Photograph taken by an individual named Iyawnna Hazzard, courtesy Copyright © 2015 University of California Museum of Paleontology. I modified the image with photoshop. Note that identification of fossil and its assignment to a geologic rock formation are my responsibility, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the University California Museum of Paleontology. |

|

|

|

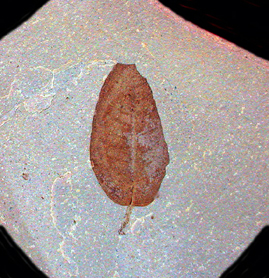

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A complete leaf of a serviceberry from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada (in actual size, 22mm long). Amelanchier hawkinsae--a species restricted to Nevada paleobotanical localities of middle Miocene geologic age, approximately 15 to 12 million years ago. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized fossil collecting at Fossil Valley is now strictly verboten. Right--Leaves still attached to the stem of the fossil equivalent of the modern Catalina ironwood (Lyonothamnus floribundus)--also called Lyon Tree--which is now restricted in native habitat solely to the Channel Islands off the coast of Southern California. Entire specimen is 58mm long. Called scientifically, Lyonothamnus parvifolius. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A complete leaf from an evergreen live oak called scientifically Quercus pollardiana (27mm long). This particular species of fossil oak is allied with the modern maul oak Quercus chrysolepis, which is presently native to the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada and the Coastal Ranges of California. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--A winged seed from a spruce, called scientifically Picean magna (15mm long), preserved alongside a smashed midge insect. This is a variety of extinct spruce whose winged seeds show a general relationship to the living Picea polita, the tiger-tail spruce now native to the volcanic soils of Japan. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A cottonwood leaf (Populus sp) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. One of a number of fossil cottonwoods from Fossil Valley. Photographer--an individual who goes by the cyber-name "harunyahya." Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Right--A winged seed from a White fir, called scientifically Abies concolor. (12mm long). From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographer unknown. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A winged seed from a spruce, called scientifically Picean magna (13mm long). This is a variety of extinct spruce whose winged seeds show a general relationship to the living Picea polita, the tiger-tail spruce now native to the volcanic soils of Japan. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--A complete leaf from an evergreen live oak called scientifically Quercus pollardiana (around 27mm long). This particular species of fossil oak is allied with the modern maul oak Quercus chrysolepis, which is presently native to the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada and the Coastal Ranges of California. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographer unknown. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

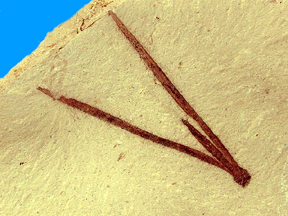

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A ponderosa pine fascicle--in botanical terminology, a bundle of needles--from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Pinus ponderosa. Photographer unknown. Fossil Valley is a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Right--An evergreen live oak leaf from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. In actual size--40mm long. Called scientifically Quercus pollardiana--the extinct Miocene equivalent of the living maul oak Quercus chrysolepis, presently native to the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada and the coastal ranges of California. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A winged seed from a spruce, called scientifically Picea sonomensis (17mm long). It's the extinct Miocene analog of the living Brewer spruce Picea breweriana, now native to northwest California and southwestern Oregon. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographed by author. Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--Two indetermined inflorescences--flowers (each about eight millimeters wide)-- from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Photographer unknown. Fossil Valley is a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A mostly complete, whole, leaf from an extinct variety of Zelkova. Called Zelkova sp. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Image courtesy a specific scientific publication. Right--A complete, whole, leaf from an extinct water oak called scientifically Quercus simulata. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Fossil Valley is a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Image courtesy a specific scientific publication. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--foliage from a member of the cypress family commonly called "Alaskan Cedar." Scientific name is Chamaecyparis nootkatensis. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Image courtesy a specific scientific publication. Right--A complete, whole, leaf from a Miocene variety of black cottonwood, called scientifically Populus trichocarpa. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Fossil Valley is a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Image courtesy a specific scientific publication. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A complete, whole, leaf from a Miocene variety of silver buffaloberry. Scientific name is Shepherdia argentea (formerly called Elaeagnus utilis). From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Image courtesy a specific scientific publication. Right--Three leaves from a Miocene variety of wild crab apple, called scientifically Peraphyllum vaccinifolia. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Fossil Valley is a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Image courtesy a specific scientific publication. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Two winged seeds from a Miocene variety of bigleaf maple. Scientific name is Acer macrophyllum. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Fossil Valley is a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Image courtesy a specific scientific publication. Right--Leaves of the fossil equivalent of the modern Catalina ironwood (Lyonothamnus floribundus)--also called Lyon Tree--which is now restricted in native habitat solely to the Channel Islands off the coast of Southern California. Called scientifically, Lyonothamnus parvifolius. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Fossil Valley is a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Image courtesy a specific scientific publication. |

|

|

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Petrified wood from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Scientifically undescribed paleobotanical material. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. |

1.jpg) |

|

|

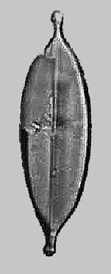

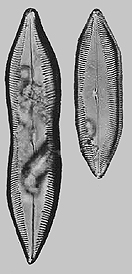

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Diatoms (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--technically called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Left to right: Anomoeoneis lanceolata; Anomoeoneis nyensis; Anomoeoneis turgida. Specimens magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. Right--Diatom (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell--techincally called a frustule") from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Fragilaria crassa1a. Specimen magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Diatom (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--techincally called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Stauroneis debilis. Specimen magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. Right--Diatom (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--technically called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Surirella spicula. Specimen magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

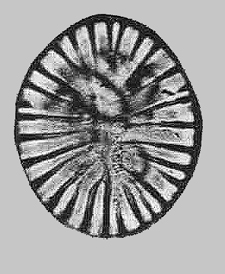

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Diatoms (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--technically called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Cestodiscus cedarensis. Specimens magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. Right--Diatom (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--technically called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Cestodiscus fasciculatus. Specimen magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

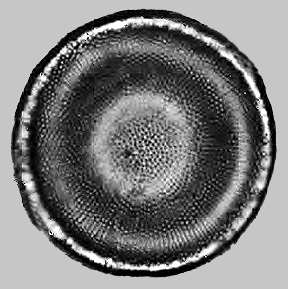

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Diatom (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--technically called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Cestrodiscus stellatus. Specimen magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. Right--Diatoms (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--technically called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Melosira crassa. Specimens magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Diatoms (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--technically called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Pinnularia esmeraldensis. Specimens magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. Right--Diatom (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--technically called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Tetracyclus radiatus. Specimen magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

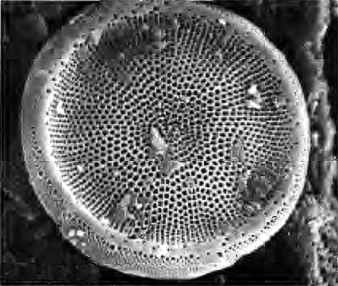

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Diatom (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--technically called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Actinocyclus cedrus. Specimen magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. Right--Diatom (microscopic single-celled algae with a silica "shell"--technically called a frustule) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Actinocyclus cedrus. Specimen magnified over 1,000 times. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Freshwater gastropods from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. All three, Vorticifex sp.; for perspective, the specimen in center is 15mm across. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--Freshwater pelecypods from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Pisidium sp. All specimens from 6 to 7mm across. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for a larger picture. Left--Freshwater gastropods from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Top row--Valvata sp. Middle row--Vorticifex sp. Bottom row--Goniobasis sp. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--Freshwater gastropods from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Top--all three, Viviparus sp; for perspective, specimen in middle is 38mm high. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Freshwater gastropods residing in their calcareous sandstone matrixes from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. all three complete shells, Vorticifex sp. Photograph by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--Two complete Viviparus sp. snails at left and lower center. Photograph by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Freshwater gastropods from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. All four, Valvata sp.; for perspective, entire specimen at left (a complete Valvata valve resting atop a Vorticiex) is about 15mm in diameter. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--Freshwater gastropods residing in their calcareous sandstone matrix from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Complete coiled specimens are Vorticifex sp. (about 15mm in diameter); whitish gastropod in roughly left-center is Valvata sp. Photograph by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Two perspectives of a chunk of freshwater gastropod coquina from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Left view shows the surface of a coquinoid calcareous sandstone packed with snail shells--both complete and broken. Image at right is a closer look at the lower right section of the photograph at left. Most abundant species present in the matrix is a coiled freshwater gastropod called scientifically Vorticifex sp., complete shells of which are roughly 15mm in diameter. Note that original shell material is here preserved intact. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Freshwater gastropods weathered in relief on a slab of calcareous sandstone from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. All coiled snails, Vorticifex sp. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. Right--Freshwater gastropods and a pelecypod from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. For perspective, the specimen at lower right (marked with letter A) is 30mm long. Photographed by author. Collected before Fossil Valley became a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is now strictly verboten. All gastropods, except specimen marked letter "D." Letter A--Viviparus sp.; Letter B (four specimens to left, and three to the right of the letter)--Goniobasis sp.; Letter C--Valvata sp.; D--A pelecypod, Sphaerium. All the rest, without lettering--Vorticifex sp. |

|

|

|

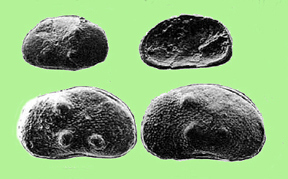

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Ostracods (a bivalve crustacean) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Dongyingia lariversi. Actual sizes of specimens--top row, left to right (exterior and interior views of different valves, respectively): 0.84mm and 1.04mm across, respectively. Bottom row--0.46 and 0.54mm across, respectively. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. Right--Ostracods (a bivalve crustacean) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Dogelinella coaldalensis. Actual sizes of specimens--left to right: 0.50mm and 1.04mm across, respectively. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Ostracod (a bivalve crustacean) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Disopontocypris hendersoni. Both valves of the same specimen. Actual sizes--0.97mm across. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. Right--Ostracod (a bivalve crustacean) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Cypridopsella esmeraldensis. Actual size of specimen--1.04mm across. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting is strictly verboten. |

a.jpg) |

|

|

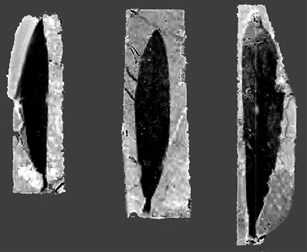

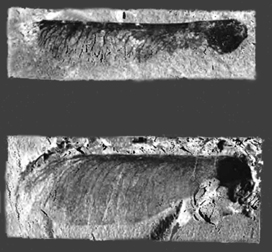

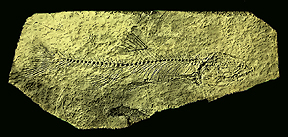

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A mostly complete freshwater fish skeleton belonging to a salmonid, which is related to salmon, char, and trout--probably its closest living relative is the Dolly Varden trout. From the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Nevada. Millimeter scale at far left. Photographed by the long-time doyen of Nevada Cenozoic Era paleobotany, the late paleobotanist Howard E. Schorn (former Collections Manager of fossil plants at the University California Museum of Paleontology). In addition to such salmonids, the Esmeralda Formation at Fossil Valley also produces members of the Cyprinidae family (minnows, chubs, European daces, carps, and chars are examples). A pharyngeal arch resembling that which belongs to a hardhead (a member of the Cyprinidae native to California) was collected from the Esmeralda Formation many years ago, as well. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. Right--A freshwater fish from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation. It's a Chub, called scientifically Gila sp.--a member of the Cyprinidae family (minnows, chubs, European daces, carps, and chars are other representative examples). Not collected in Fossil Valley, proper, but the specimen is fully representative of the Cyprinidae known from Fossil Valley's Esmeralda exposures. Actual size of specimen--140mm long. Photograph is from a specific technical document. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area; unauthorized collecting there is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

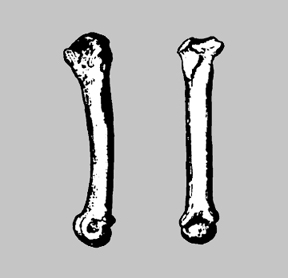

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Two line drawing views of the same canid (dog family) metacarpal (one of the foot bones) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Actual size--70mm long. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. Right--Line drawing of a portion of a felid (cat family) humerus (long front-leg limb bone) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Actual size--150mm long. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

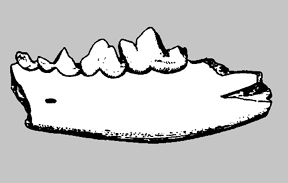

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Line drawing of a Ring-tailed cat lower jaw segment, with dentition, from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Bassariscus nevadensis. Actual size--32mm long. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. Right--Line drawing of a beaver jaw segment/mandible, with dentition, from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Dipoides tortus. Actual size--32mm long. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

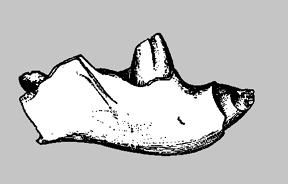

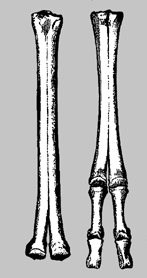

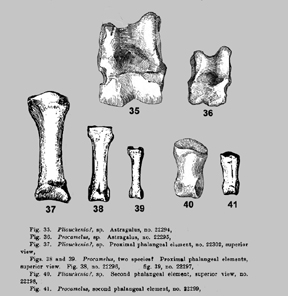

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Line drawings of rhinoceros and horse astragali (commonly called the ankle bone) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. Left to right: Left and middle--astragali from a rhinoceros called Aphelops sp. (actual sizes--right, 100mm across; middle, 60mm across); far right--astragalus from a horse called Hypohyppuss osbouri (25mm across). Right--Line drawing of articulated (skeletal elements in their natural anatomical relationships) horse front limb bones from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Hypohippus nevadensis. Actual size of specimen--350mm long. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

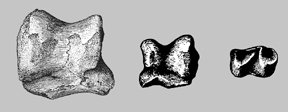

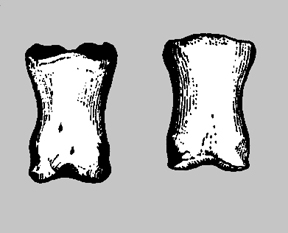

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Line drawings of horse proximal phalanges (toe bones) from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Merychippus sp. Actual sizes--both 35mm long. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. Right--Line drawings of camel foot bones from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Procamelus gracilus. Left to right: Cannon bone, posterior limb--14 centimeters long. Right: metapodials and phalanges, anterior limb--15 centimeters long. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Line drawings of camel foot bones from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Procamelus sp. and Pliauchenia sp. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. Actual sizes of specimens: Top--left to right: 58mm and 37mm long, respectively. Bottom--left to right: 65mm; 50mm; 35mm; 40mm; and 28mm long, respectively. Right--Line drawing of a pronghorn antler from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Merycodus furcatus. Actual size--65mm long. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. |

|

|

|

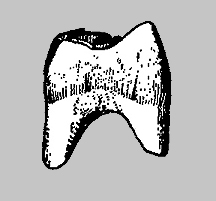

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Line drawings of pronghorn teeth and jaw from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Merycodus furcatus. Drawings at top of image represent views of the teeth grinding surfaces. Actual sizes of bottom specimens--left to right: 35mm long; 10mm high; and 8mm high, respectively. Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. Right--Line drawing of a Mountain beaver molar from the middle Miocene Esmeralda Formation, Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada. Aplodontia sp. Actual size--5mm long (high). Image taken from a specific technical publication. Fossil Valley is now a federally protected area. Unauthorized collecting in Fossil Valley is strictly verboten. |

|