|

Among the more paleontologically important Earth Science

localities in California is Inyo County--an astoundingly vast,

often impressively rugged region of great elevation extremes

situated in approximately the east-central area of the Golden

State that boasts not only the lowest point in the North America

(Badwater Basin at 282 feet below sea level, in Death Valley

National Park), but also the highest place in the contiguous

United States (Mount Whitney, at an altitude of 14,505 feet).

Distributed across Inyo County are numerous justifiably famous

fossil-bearing regions, including--but of course not limited

to: Death

Valley National Park (features world-class suites of Cambrian-through

Permian Period invertebrate animal material, including the practically

incomparable early Cambrian Waucoba

Spring Geologic Section; plus, many Cenozoic Era vertebrate

skeletal preservations and associated ichnofossils--mammalian

trackways); the Nopah

Range, positioned within California's Mojave Desert Geomorphic

Province, where the lower Cambrian Carrara Formation yields plentiful

trilobites, an extinct arthropod; Westgard

Pass in the White-Inyo Mountains early Paleozoic Era stratigraphic

complex, a world-renowned geologic wonderland which remains one

of the best places on earth to find early Cambrian archaeocyathids--an

enigmatic invertebrate animal, usually considered a variety of

calcareous sponge--in addition to locally common trilobites,

brachiopods, annelid and arthropod trails, and primitive echinoderms;

Cerro

Gordo Grade along the eastern flanks of the Inyo Mountains

east of Keeler, adjacent to dry Owens Lake, where abundant ammonoids

and pelecypods--plus, some shark teeth and terrestrial plants

occur in the upper Mississippian Chainman Shale, roughly 325

million years old; Union

Wash (another paleontologicly rewarding locality found within

a major dry drainage tributary of the eastern slopes of the Inyo

Mountains; lies in the vicinity of Lone Pine, directly east of

Mount Whitney--a ne plus ultra place to find abundant cephalopod

ammonoids in the lower Triassic Union Wash Formation, with the

back-drop of the glacier-gouged Sierra Nevada skyline in dramatic

view to the immediate west); and the

Coso Range (at the southern end of California's Owens Valley,

where vertebrate fossils some 4.8 to 3.0 million years old can

be observed in the Pliocene-age Coso Formation: it's a paleontologically

noteworthy place that yields many species of mammals, most particularly

the remains of Equus simplicidens, the Hagerman Horse,

named for its spectacular occurrences at Hagerman Fossil Beds

National Monument in Idaho; Equus simplicidens is considered

the earliest known member of the genus Equus, which encompasses

the modern horse and all other equids).

Yet another Inyo County place of extraordinary paleontological

productivity can be explored at Mazourka Canyon, a major defile

that drains an appreciable area of the western flanks of the

Inyo Mountains a number of miles east of Independence, the county

seat of Inyo County. Here can be examined in full view of the

prominent Sierra Nevada to the immediate west one the more reliably

fossiliferous stratigraphic successions of Ordovician, Silurian,

and Devonian Period rocks in all the western reaches of the Great

Basin Desert Geomorphic Province. Its often well preserved early

to middle Paleozoic Era fossil material, advantageously amenable

to recovery by professional Earth Scientists and amateur paleontology

enthusiasts alike within the presently accessible Mazourka Canyon

corridor (always check with the local Bureau of Land Managment,

of course, to determine the most up-to-date status of fossil

localities that occur on public lands), is in the western US

ordinarily particular to correlative stratigraphic sections exposed

several hundred miles east of the Inyo Mountains, throughout

central and eastern Nevada to western Utah. Representative fossil

varieties present at Mazourka Canyon constitute a genuinely diverse

assemblage of classic early to middle Paleozoic Era invertebrate

and primitive vertebrate animal remains, in addition to interesting

algal structures. Expect to encounter, for example: Girvanella,

an extinct genus of blue-green algae; the usually rare Verticillopora

dasycladacean algae (a large green algae--it's quite plentiful

in the Silurian-age Mazourka Canyon section, actually); annelid

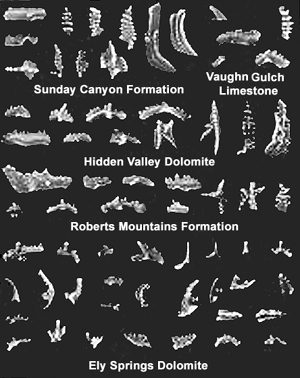

(worm) trails; articulate brachiopods; bryozoans; conodonts (minute,

roughly tooth-shaped calcium phosphate specimens, unrelated to

modern vertebrate jaws, that served as a feeding apparatus for

an extinct lamprey eel-like organism--recovered only from insoluble

residues remaining from dissolution of carbonates and shales

in a dilute organic acid solution--usually glacial acetic acid);

rugose and tabulate corals; echinoderms (crinoid ossicles and

columnals; and cystoid echinoderm segments and columnals); graptolites

(an extinct hemichordate--a primitive vertebrate animal; Mazourka

Canyon remains one of California's premiere producer of graptolites);

and trilobites.

Throughout Mazourka Canyon's regional distribution of sedimentary

deposition, all seven Periods of the Paleozoic Era are excellently

represented--that is to say, one can expect to encounter in ascending

order of relative age nicely exposed rocks from the Cambrian,

Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Mississippian, Pennsylvanian,

and Permian geologic Periods. Unfortunately, as one must ultimately

come to recognize, individual Mazourka stratigraphic formational

units of Cambrian, Mississippian, Pennsylvanian, and Permian

age contain, in general, only relatively uncommon exceptional

biological preservations; sedimentary accumulations of the Ordovician-Silurian-Devonian

Paleozoic succession, on the other hand, provide locally abundant,

and for the most part wonderfully preserved fossil material.

For example--except for a solitary anomalous example (the Lead

Gulch Limestone)--among the Cambrian stratigraphic rock units

present within territory that is by common convention assigned

to Mazourka Canyon, several specific renowned formations, so

richly fossiliferous elsewhere in Inyo County (the Harkless Formation,

Saline Valley Formation, Mule Spring Limestone, and Monola Formation,

for example; indeed, in not a few instances paleontologists the

world over visit such fantastic localities quite regularly),

bear but sporadic occurrences of superior paleontologic evidence.

In Mazourka Canyon, the Cambrian Period (approximately

541 to 484 million years ago) is represented in ascending stratigraphic

successional order by the following rock intervals (unless otherwise

noted, they contain relatively sparse paleontology): lower Cambrian

Harkless Formation (bears occasional fucoid markings preserved

in curious configurations that suggest annelid trails); lower

Cambrian Saline Valley Formation; lower Cambrian Mule Spring

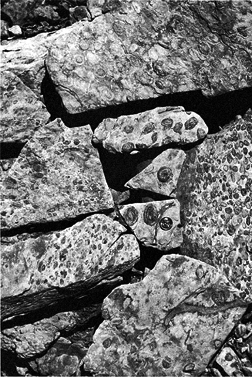

Limestone; middle Cambrian Monola Formation; middle to upper

Cambrian Bonanza King Dolomite (contains locally obvious oval

to circular bodies that represent an extinct variety of blue-green

algae paleontologists call Girvanella; minor occurrences

of presumed annelid fucoid markings present, as well); upper

Cambrian Lead Gulch Formation (an exception to the usual Mazourka

Cambrian rule of rare significant paleontological preservations:

bears the agnostid trilobites Homagnostus sp. Pseudagnostus

sp. and Loganellus sp., in addition to acrotretid

brachiopods and various echinoderm parts--dissociated cystoid-type

ossicles); and the Upper Cambrian Tamarack Canyon Dolomite.

Among rocks of Mississippian, Pennsylvanian, and Permian

Period age in Mazourka Canyon (European stratigraphers consider

the North American-designated Mississippian and Pennsylvanian

Periods, combined, their equivalent of the Carboniferous, of

course) both the upper Mississippian Perdido Formation and overlying

Rest Spring Shale (roughly 335 to 325 million years old) actually

do contain surprising localized concentrations of rather interesting

invertebrate animal remains, in addition to a few botanic preservations.

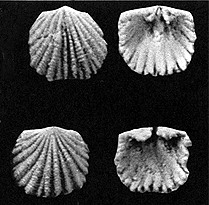

Within the Perdido, for example, identifiable specimens of Strophomenoid

brachiopods, horn corals, bryozoans, trilobites, and pelmatozoans

(crinoid ossicles and columnals) have been recovered; the geologically

younger Rest Spring Shale also produces a pretty decent diversity

of forms, including: Cravenoceras and Cravenoceratoides

cephalopod ammonoids; gastropods; pelecypods; brachiopods; crinoid

plates; and plant fragments (presumably from a nearby swamp paleoenvironment).

The overlying late Pennsylvanian Keeler Canyon Formation (about

290 million years old), despite its prolific paleontologic content

elsewhere in Inyo County, yields at Mazourka Canyon only occasional,

frustrating indications of poorly preserved fusulinids, an extinct

single celled animal that secreted a distinctive wheat-shaped

shell with a geometrically intricate internal structure. Above

the Keeler Canyon lies the Permian Owens Valley Formation (298.9

to 252.17 million years old) that only a few miles removed from

Mazourka Canyon produces beaucoup brachiopods, bryozoans, corals,

and fusulinids--yet, within the Mazourka corridor it is mysteriously

lacking paleontology.

Fortunately for folks invigorated with fossil-finding enthusiasm,

Mazourka Canyon provides numerous reliable opportunities to collect

quality quantities of identifiable, fabulously preserved Paleozoic

Era invertebrate animal specimens. The recommended geologic rock

formations in which to concentrate one's exploratory investigations

remain restricted to those deposited approximately 485

to 415 million years ago during the Ordovician, Silurian,

and Devonian Periods. And within Mazourka Canyon, that specific

stratigraphic interval would of course include the following

rock units, in ascending order of geologic age (oldest to youngest):

lower Ordovician Al Rose Formation; lower to middle Ordovician

Badger Flat Limestone; middle Ordovician Barrel Spring Formation;

late middle Ordovician Johnson Spring Formation; upper Ordovician

to early Silurian Ely Springs Dolomite; lower Silurian to lower

Devonian Vaughn Gulch Limestone; and the lower to middle Devonian

Sunday Canyon Formation.

Where to first concentrate fossil searches is an individual

decision, naturally enough, possibly predicated on what particular

varieties of paleontological forms one wishes to hunt with immediate

urgency; suggested organismal exemplars to choose from include

algae, brachiopods, bryozoans, conodonts, corals, echinoderms,

gastropods, graptolites, and trilobites. Still and all, probably

a rewarding initial fossil-oriented reconnaissance would be to

the lower Ordovician Al Rose Formation (approximately 485 to

480 million years old).

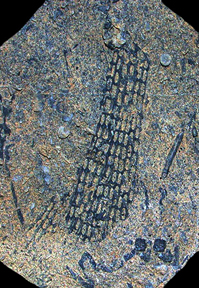

The Al Rose enjoys a richly deserved, exalted reputation

for yielding up some superior graptolites, trilobites, and brachiopods.

Indeed, it's one of California's premiere producers of graptolites,

an extinct variety of hemichordate (by definition, a primitive

vertebrate).

Graptolites first appear in the geologic record during

the middle stages of the Cambrian Period, some 505 million years

ago. Even though they persisted all the way up to the late Mississippian

age, or roughly 325 million years ago, most species of graptolites

had already become extinct by the latest Devonian Period 35 million

years earlier. Graptolites achieved their highest degree of success

during the Ordovician Period, when they attained worldwide distribution

by adapting with ingenuity to three distinct modes of life. One

order of graptolite, for example--the fan to leaf-shaped dendroids--led

a sessile life attached to the sea floor, apparently straining

the marine waters for microscopic organisms. Another type developed

a special flotation device which allowed the graptolite colony,

termed a rhabdosome, to drift in the open ocean; and a third

kind solved its own planktonic challenge by attaching itself

to floating strands of seaweed to hitch a free ride through the

open ocean in search of better feeding grounds; presumably it

too strained the sea waters for microscopic particles of food.

In all three examples of graptolitic adaption, the actual

colonial animal lived inside the minute rows of cups called thecae

that developed along each individual segment of the rhabdosome;

technically, these segments are called a stipe. The tiny saw-tooth

compartments that housed the graptolite animals along the stipe

show to best advantage under magnifications of ten or more power.

Thus, a good-quality hand lens is indispensable in order to gain

a detailed and aesthetic appreciation of graptolite specimens.

The exact zoological classification of graptolites has

presented a serious challenge to paleontologists. Early investigators

referred graptolites to such disparate groups as coelenterates

or bryozoans; yet, there certainly was no unanimity of opinion

among fossil specialists throughout the 19th century. The breakthrough

came when some perfect, three dimensional specimens were etched

out of cherts using powerful brews of acids around 1948. Paleontologists

then realized that the graptolite colony most closely resembled

the modern pterobranch, a tiny marine hemichordate, which by

definition is a primitive chordate whose notochord (a spine-like

notch) is restricted to the basal part of the head.

The Al Rose Formation is composed primarily of some 400

feet of clastic siltstones, mudstones, and shales that typically

weather to shades of orange and red-brown, with subordinate carbonate-dominated

intervals of arenaceous medium-gray to bluish gray limestones.

Almost all of the paleontology derives from the colorful clastic

unit. In some places the Al Rose is a genuine bonanza body, packed

with showy, exquisitely detailed graptolites that exhibit an

aesthetically pleasing "golden glow" of preservational

contrast on a darker shale matrix--impregnated as they are by

the mineral limonite, a hydrated iron oxide (FeO(OH)·nH2O).

Fossil goodies identified from the lower Ordovician Al

Rose include the following: brachiopods--Lingulella, plus

several additional species not yet formally described in the

scientific literature; the trilobites Globampxy trinucleoides,

Peraspis erugata, Shumardia, Trigonocerca,

Anthrorhacus sp., Cryptolithus sp., and Hypermercaspis

brevifrons; the graptolites Tetragraptus bigsby, Tetragraptus

reclinatus, Tetragraptus serra, Phyllograptus anna,

Phyllograptus ilicifolius, Didymograptus protobifidus

bifidus, Didymograptus protoindentis, Didymograptus

artus, and Didymograptus nitidus; gastropods; two

varieties of pelmatozoan echinoderms; Chondrites ichnofossils

(a trace burrow); and Conulariids (an extinct type of scyphozoan

cnidarian).

Lying directly above the lower Ordovician Al Rose Formation

is the exceptionally fossiliferous middle Ordovician Badger Flat

Limestone, which in part most certainly correlates stratigraphically

with the world-famous Antelope Valley Limestone exposed in western

to central Nevada. Blue-gray limestone is the dominant lithology,

with irregular lenses and layers of light-gray, orange, and red-brown

silty and marly sections. Most its 500 to 600 foot thickness

is accurately described as limestone, but specimens studied in

microscopic thin section reveal abundant clastic quartz grains,

as well.

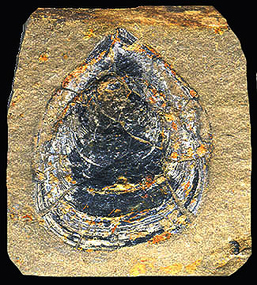

The Badger Flat Limestone is notably fossiliferous. In

an interval roughly 100 to 200 feet below the top of the formation,

Palliseria robusta gastropods up to three inches in diameter

are so regularly abundant that they constitute a mappable horizon.

Elsewhere, numerous additional kinds of invertebrate animals

can be recovered from the well exposed middle Ordovician carbonate

accumulations. These include: the extinct blue green algae Girvanella,

and an extinct green algae called Recepticulites; the

brachiopods Orthombonites mazourkaensis, Orthambonites

patulus, Orthidiella sp., Rhysostrophia nevadensis,

and Rhysostrophia occidentalis; bryozoans (two genera);

conodonts; a favositoid coral; the cephalopods Rewdemannoceras

sp. and Rossoceras sp.; cystid echinoderms; gastropods

of a kind different from the large Palliseria; sponges

that can be assigned to Calycocoelia sp.; and trilobites

identified as belonging to--a bathyurid, Isotelus, an

Asaphid, Achatella, a pliomerid, Pseudomera, and

a dalmanitid.

Next up in the Mazourka Canyon Ordovician-Silurian-Devonian

stratigraphic sequence, right above the Badger Flat Limestone,

is the middle Ordovician Barrel Spring Formation--an aggregate

of 130 feet of predominantly light-colored limestone, impure

quartzite, and siltstone (lower member) overlain by distinctive

red-brown-weathering shale, mudstone, and siltstone (upper member).

While Barrel Spring fossils are not reliably well preserved,

readily identifiable remains are nevertheless rather common throughout

the lower portions of the upper terrigenous member. Organisms

described from the Barrel Spring include: the trilobites Remopleurides,

Isotelus spurius, Lonchodomas, and Ampyx; the brachiopods

Valcourea cf. V. plana, Orthambonites decipiens, Hesperorthis,

Hesperorthis cf. H. dubia, Plaesiomys, and Rafinesguina;

bryozoans; graptolites, Dicellograptus sextans; and pelmatozoan

echinoderm columnals.

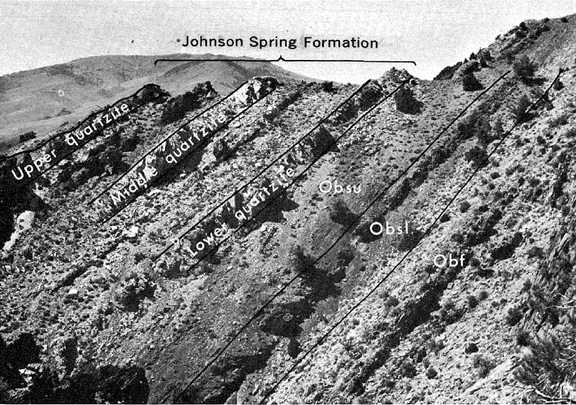

Overlying the middle Ordovician Barrel Spring Formation

is the highly fossiliferous late middle Ordovician Johnson Spring

Formation. It's approximately 400 feet thick, on average, consisting

in most measured geologic sections of three white to gray orthoquartzite

layers (a heat and pressure-altered sandstone, which here contains

vertical phoronid worm borings called Skolithos) interbedded

with five medium-gray to medium dark-gray carbonate beds (limestone

and dolomite). The carbonate rocks of the Johnson Spring Formation

contain a large and varied fossil fauna in which corals are predominant.

Identified specimens include: the extinct green algae Recepaculites;

vertical ichnofossil borings created by an extinct phoronid worm

called Skolithos; a sponge, Anthaspidella inyoensis;

the corals Streptelasma tennysoni, Paleophyllum mazourkensis,

Favistella cf. F. discreta, Grewingkia whitei,

Brachyelasma bassleri, Lichenaria sisyphi, and

Eofletcheria kearsargensis; the brachiopods Zygospira,

Nicolella, Ptychopleurella arthuri, Sowerbyella

merriami, and Desmorthis; echinoderm columnals (crinoids);

bryozoans; gastropods; pelecypods; and cephalopods.

What's additionally fascinating about the Johnson Spring

Formation at Mazourka Canyon is that its stratigraphically correlative

lateral rock equivalent is none other than the world famous,

though uniformly unfossiliferous middle to lower late Ordovician

Eureka Quartzite--certainly one of the most widespread early

Paleozoic Era rock units in all the Great Basin Desert. Not only

has it been recognized throughout Death Valley and Nevada, but

it also shows up in geologic sections as far away as Millard

County in western Utah.

For decades, scientists have speculated on the original

environment of deposition of the Eureka Quartzite, an unusually

thick bed of heat and pressure-crushed sandstone. Many models

have been analyzed, but no one explanation seems to answer all

the questions.

The main problem for geologists is to satisfactorily account

for such a massive, persistently uniform zone of practically

pure metamorphosed sandstone that occurs over hundreds of square

miles. It hasn't been easy. After much debate on the subject,

earth scientists remain puzzled and intrigued, although recent

investigations seem to show that the Eureka Quartzite accumulated

some 465 million years ago as clean, well-sorted beach sand along

the shores of a shallow sea during the middle portion of the

Ordovician Period.

Lying in stratigraphic positional contact directly above

the Johnson Spring Formation is the upper Ordovician to lower

Silurian Ely Springs Dolomite. This is some 590 feet of mostly

medium gray to dark gray magnesium carbonate typically preserved

in individual beds one to six inches thick, with interesting

associated chert bodies that sometimes contain sponge spicules.

While it's never really been universally appreciated as an especially

rich receptacle for the retention of fossils at Mazourka Canyon

(exposures of the Ely Springs Dolomite in eastern Nevada, though,

frequently yield beaucoup paleontology), the Ely Springs nevertheless

actually does indeed contain an important fauna of sponge spicules,

Streptelasma corals, crinoidal debris, and a large selection

of conodonts.

The conodonts are a fascinating fossil type. Measuring

only one to three millimeters long, conodonts are minute jaw-like

specimens that for over a century were thought to have come from

worms or perhaps some primitive extinct species of fish. They

first appear in the geologic record during the Late Cambrian

(roughly 500 million years ago) but are especially characteristic

of the Ordovician through Mississippian Periods. Although they

persisted well into the Triassic Period of the Mesozoic Era--the

age of reptiles--most conodonts had become extinct by the close

of the Permian Period 252 million years ago.

Because they so closely resembled miniature jaws, it was

easy for paleontologists to assume that this had been their original

function; a few scientists simply shrugged them off as worm jaws,

despite the fact that the chemical compositions of worm jaws

and conodonts are unmistakably different. Talk about a fossil

that got no respect! More serious investigators theorized that

they might have belonged to the gill apparatus of several extinct

species of fish. Another nice try. Most paleontologists agreed,

though, that the conodont animal, whatever it was, must have

been soft-bodied, simply because no other evidence of hard parts

was noted in the same sediments that yielded conodonts.

Nobody had seriously expected to find the actual conodont

animal--after all, a hundred-plus years of collecting couldn't

be wrong--but at last, it appeared, that the incredible discovery

had been made in 1968 in the Little Snowy Mountains of Montana.

Here, in the fine-grained shales of the transitional Late Mississippian

and Early Pennsylvanian deposited 320 million years ago, the

mystery, for short spell at least, appeared to be resolved once

and for all. What scientists had recovered from the Montana locality

was a small fish-shaped chordate (it seemed to possess a primitive

spinal cord, although this was more like a partial notch just

behind the head), which had a single fin on its back for stability

and a tail fin for swimming. Based on the first 24 carbonized

outlines of the body cavity unearthed, the purported conodont

animal averaged a little under 12 millimeters in length. The

phosphatic, jaw-like conodont fossils themselves, lying supposedly

in-place with the preserved remains of the animal, were restricted

to the interior of the body cavity, about midway between the

head and tail. Scientists immediately conjectured that the conodont

structures served to circulate water currents through the body

and acted as sieves, as well.

But, something was wrong with the entire scenario. In the

harsh reality engendered through meticulous study of the putative

conodont animal, scientists soon realized that, while the conodont

structures were indeed confined to the interior of the body cavity,

those jaw-like fossils were not aligned in a natural, in-place

relationship after all. The Montana "conodont" animal

turned out to be nothing more than a particularly ravenous and

effective conodont predator. Sure, the Montana critter had all

kinds of conodont structures inside the body cavity, but the

conodonts got there through ingestion.

Back to square one. Fortunately, conodont researchers are

incredibly persistent individuals. And that persistent attitude

eventually paid off: in 1982, Dr. E. N. K. Cradlesong finally

discovered the actual conodont animal in Carboniferous (the European

equivalent of the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian Periods combined)

rocks in Scotland. The conodont animal also turned up in some

Ordovician-age strata exposed in South Africa. In both instances,

the creature is a lamprey eel-like organism with an elongated

body; associated with the fossil are imprints of chevron-shaped

muscles along with a trace of the notochord, large paired eyes,

plus a caudal fin strengthened by radials. The calcium phosphate

conodont structures (called denticles by conodont specialists)

lie in the head region, perhaps at the entrance of the pharynx.

Presumably they represent a unique feeding apparatus unrelated

to modern jaws.

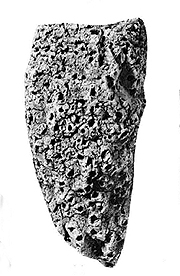

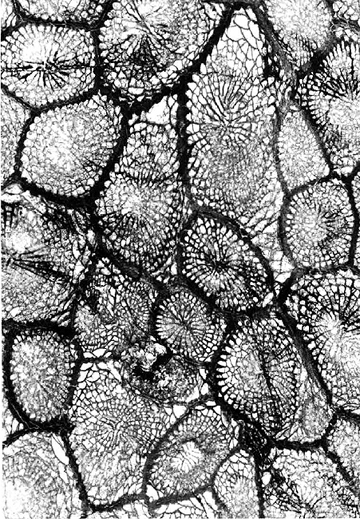

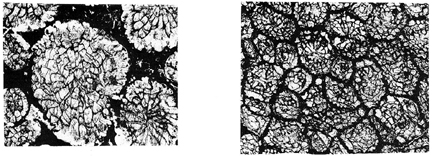

Next youngest geologic rock formation exposed at Mazourka

Canyon, resting atop the Ely Springs Dolomite, exhibits such

extraordinary fossil content that most visitors would certainly

categorize it as a genuine paleontological crown jewel of the

entire area: the lower Silurian to lower Devovian Vaughn Gulch

Limestone. Its diverse and well preserved fauna--invariably silicified

(that is, replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide) and imbued

an aesthetically attractive reddish-brown on a dark blue-gray

limestone matrix by the mineral limonite--has justifiably attained

legendary proportions among fossil aficionados in the western

United States. For purposes of propaedeutic pedagoguery, for

instance--instructing their students in the foundational principles

of Historical Geology--geology professors from community colleges

and universities (AKA, institutions of higher learning) throughout

the West regularly schedule field trips to the Vaughn Gulch exposures;

consequently, opportunities obviously arise there for lots of

folks to run off with loads of sample fossil material, although

one must note that at last field check it's still a productive

place to examine abundant showy, readily recognizable Paleozoic

Era sea life.

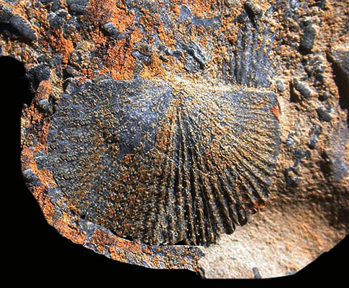

The Vaughn Gulch Limestone classically consists of about

1,500 feet of dominantly medium to dark gray limestone that additionally

incorporates subordinate shades of red, yellow, and orange; minor

shale partings typically separate the most diagnostic rock variety

present--a stunningly fossiliferous bioclastic limestone that

tends to form ledges crowded with the following forms: algae--Verticillopora

annulata; brachiopods--Gypidula, Athyris, Trematospira,

Schizophoria, Plectatrypa sp., Camarotoechia,

Atrypa, and Eatonia bicostata; such rugose and

tabulate corals as Australophyllum, Strombodes,

Favosites, Chonophyllitm, Rhisophyllum, Heliolites,

Alveolites, Cladopora, large cyathophyllids,

a small tryplasmid, a pycnostylid, Aulacophyllum,

Acinophyllum, Diplophyllum, Kyphophyllum nevadensis,

Phacelophyllum, Camerotoechia, Syringopora,

and Disphyllum; sponges--stromatoporoids and Hindia;

bryozoans; conodonts; and pelmatozoan and crinoidal echinoderms.

The youngest--and therefore final--significant fossil-bearing

unit within Mazourka Canyon's early to middle Paleozoice Era

successional complex is the lower to middle Devonian Sunday Canyon

Formation (around 415 million years old), which stratigraphically

speaking intertongues with and overlies the slightly younger

uppermost Vaughn Gulch sedimentary deposits. In its traditionally

familiar outcropping aspect, the Sunday Canyon weathers to form

rather poorly exposed slopes composed of thin flaggy fragments

of calcareous siltstone, calcareous shale, and argillaceous limestone

in shades of light gray to yellow and orange.

And it bears lots of invertebrate fossils. The Sunday Canyon

Formation faunal list, for example, includes at least six species

of the highly prized Monograptus graptolites, which developed

distinctive rhabdosomes that resemble tiny sawblades. This is

the westernmost outcropping of Mongraptus-producing strata

in the US, by the way. To find comparable, correlative lower

Devonian graptolite-yielding rocks to investigate, you'd have

to travel a few hundred miles east of Mazourka Canyon to the

Roberts Mountains Formation in central Nevada. Sunday Canyon

graptolite species present include: Monograptus dubius;

Monograptus tumescens; Monograptus vomerirnus;

Monograptus vulgaris; Monograptus scanius; Monograptus

uniformis, and Monograptus hercynious. Also well respresented

in the Sunday Canyon geologic sections are rynchonellid brachipods;

ostracods; sponge spicules; tentaculites--Tentaculites cf.

T. bellulus (taxonomic classification uncertain, but it could

be related to the modern-day pteropods, the sea snails); conodonts;

and corals--Alveolites, Favosites, Ceriod rugose

corals, cylindrical rugose corals, horn corals, Thamnopora

sp., and Cystiphyllum.

While fossil prospecting at Mazourka Canyon, it is fitting

to consider that before the great neighboring Sierra Nevada was

uplifted to its present impressive elevations, before it was

even a minor protuberance on the face of the earth, Mazourka

Canyon's fossil organisms now situated within its shadow had

already been covered over by countless primal ooze deposits at

the bottoms of unknown numbers of successive Paleozoic Era seas

some 541 to 252 million years ago. Eventually, through the ceaseless

invisible activity of passing vanished time, geologic forces

successfully thrust both the now lithified sedimentary beds of

those long-lived oceans and the younger, once-buried solidified

magma of the batholithic Sierra several thousands of feet above

sea level.

Now the inevitable, the inexorable laws of erosion take

their turn at the rocks. And yet, while standing atop Mazourka

Canyon's fossil beds--inspecting an outcrop of 485 to 415 million

year-old sedimentary rock, with the seemingly adamantine peaks

of the Sierra in bold relief against the western skyline--it

is perhaps difficult to believe that all mountain ranges, including

the surely eternal Sierra, must someday be no more. They must

be leveled to a plain, just as countless nameless ranges have

been so reduced in the geologic past.

But perhaps another sea will have its day atop their former

glory, and new creatures may stay alive in the rocks left behind,

to rise with the mountains of a yet-distant age to the delight

of future fossil hunters.

|