|

Many species of plants and animals have become extinct

throughout the geologic past. Ammonites, trilobites, and dinosaurs

are among the more familiar types whose vanished representative

lineages now famously reside within the rocks of the earth's

crust. Still, despite the fact that such sensational, long-lived

species died out, the larger grouping or classification of animals

to which they belonged continues to survive to this date. The

ammonite, for example, was a cephalopod mollusk--rather distantly

related to our modern day chambered nautilus; the trilobite,

in turn, belonged to a scientific phylum called Arthropoda, a

phylum that includes such successful relatives as insects, crabs,

crustaceans, and spiders; and the dinosaurs of course were vertebrate

animals, whose backboned kinds are very much alive and well.

While each of the above-listed creatures became extinct

for varying paleobiological reasons, the broader category, or

phylum to which they belonged has survived. And, as far as paleontologists

can determine, virtually all the major groups of animals present

during the dawn-age Cambrian Explosion of approximately 535 to

510 million years ago, when there occurred a phenomenal, unprecedented

radiation of biological diversification, are still alive today--despite

the fact that capricious culling periodically eliminates innumerable

species throughout geologic time.

A notable exception to this pattern of persisting phylum

survival is the paleontological occurrence of curious critters

paleontologists call salterella and Volborthella. They're

invertebrate animals exclusive to the early Cambrian that secreted

conical to ice cream cone-shaped shells roughly a quarter inch-long

long; and they're now placed into their own unique phylum called

Agmata, a phylum that went belly-up, extinct, approximately 510

million years ago--among only a select few of the major taxonomic

categories of animals ever to vanish completely, leaving no discernible

descendants or relatives.

To put this in perspective, the extinction of an entire

phylum such as Agmata is analogous to having all the corals,

for example, disappear from our oceans--or, every animal with

a backbone suddenly gone forever. By all speculative accounts,

this was a terribly traumatic event in the history of our planet.

Prime hunting grounds for Agmata small shelly fossils include

the Great Basin wilds of western to central Esmeralda County,

Nevada.

Yet another fascinating animal preserved in rocks exclusively

of early Cambrian geologic age is the enigmatic archaeocythid,

an invertebrate type that along with Agmata salterella-Volborthella

and Olenellid trilobites thrived in earth's warm shallow

seas roughly 528 to 510 million years ago. Although those creatures

never survived the early Cambrian age, only the Agmata represent

a complete, unique phylum that went extinct. Olenellid trilobites

and archaeocythids belong to the living phyla Arthropoda and

Porifera (the sponges), respectively.

Still and all, not too many years ago a consensus of invertebrate

paleontologists considered archaeocyathids members of their own

unique Phylum called Archaeocyatha, preferring to count them

among the select few phyla ever to go belly-up, to vanish forever

with no known modern biological affinity.

The archaeocyathid was an exclusively marine invertebrate

animal that never survived beyond the early Cambrian of the Cambrian

Period; it goes absent from the geologic record around 510 million

years ago. Yet, during a life span of perhaps "only"

18 million years (roughly 528 to 510 million years) it was able

to attain worldwide distribution while developing into scores

of different species. In morphological aspect, an archaeocyathid

has been variously described as a peculiar cross between a coral

and a sponge. White it admittedly reveals obvious similarities

to both, it is in fact decidedly different in many key delineating

comparisons.

Pioneering early Cambrian investigators separated almost

immediately into two warring camps over the exact zoological

classification of the archaeocyathid. That is to say: just where

exactly should one place the animal--is it a coral or sponge?

Some paleontologists argued in favor of the coral category (see

the classic 1868 publication "On a remarkable new genus

of corals" in American Journal of Science, 2nd service,

volume 46, pages 62-64), while others--the majority opinion,

actually--vociferously proclaimed that it most closely resembled

a sponge; hence the ubiquitous, "endearing" term "pleosponge"

came about to describe the archaeocyathid, a designation still

found in many older textbooks on invertebrate paleontology.

Although it's true that both battling camps could adduce

compelling evidence to support their views, all the controversy

occurred before any serious analysis of the archaeocyathid was

undertaken. When some especially well preserved specimens were

finally examined with that proverbial fine-toothed comb, paleontologists

came to the conclusion that, yes, while the archaeocyathid did

show apparent similarities to both corals and sponges, it was

indeed sufficiently different from coral coelenterates and typical

Porifera to warrant placement in a new, separate phylum--then

known as Archaeocyatha.

That zoological classification of archaeocyathids as a

distinct, unique phylum lasted for several decades. When somebody

named a new species of archaeocyathid, the official peer-reviewed

scientific paper in which the formal description appeared always

placed an archaeocyathid type specimen within the phylum Archaeocyatha.

In recent years, though, rigorous cladistic phylogenetic analysis

nests archaeocyathids pretty convincingly among the Porifera--the

sponges; more specifically, it is now usually considered an extinct

calcareous sponge--the first shell-secreting member of the phylum

Porifera to appear during the Cambrian Explosion, and the very

first known sponge to go extinct, disappear completely from the

geologic record.

Since the actual archaeocyathid soft-bodied animal has

never been found preserved, researchers base their conclusions

concerning the creature on study of the available fossil shell

material. The archaeocyathid secreted a conical to cup-shaped

calcium carbonate structure typically half an inch to three inches

longs, and one-eighth to one inch in diameter. A few aberrant

species can reach a foot or more in length, however. Some varieties

in the class Irregularia began to sport wildly radiating, branching

shell designs, a feature which distinguishes them from all other

kinds of archaeocyathids. Most, though, retained their conical,

elongated configuration right up to the end of their reign. Apparently

the creature led a sessile life attached to the sea floor; some

types sometimes formed minor reef-like communities. As a matter

of fact, it seems to have been the very first Cambrian Explosion

shell-bearing animal to develop a quasi-reef, or biohermal structure

on the sea floor, a life-style greatly impoved upon by the corals,

which succeeded the archaeocyathid in the geologic record during

Ordovician Period times.

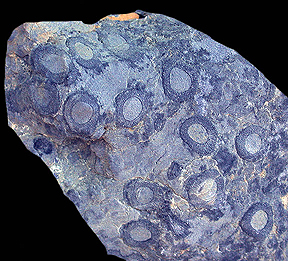

Typically, archaeocyathids formed "gardens" in

the shallow early Cambrian seas, parallel to the ancient coastlines,

where they probably fed by filtering for microscopic plants and

animals, similar to the habits of present day sponges, corals,

bryozoans, brachiopods, and barnacles. Their shell was extremely

fragile--it is indeed miraculous that we have as many complete

specimens to study as we do--and they disdained with a passion

any degree of muddy water. It is conjectured that they reproduced

by giving rise to free-floating larvae that swan about for a

time before settling to the sea floor. Additionally noteworthy

is that sometimes seen preserved with archaeocyathids are the

remains of cyanobacterial blue-green algae, suggesting some degree

of symbiotic relationship.

All archaeocyathids became extinct by the close of the

early Cambrian, approximately 510 million years ago. They left

no discernible descendants. They remain the only major group

of sponges to leave no living representatives. In North America

and Australia, extinction of the archaeocyathids coincides with

the disappearance of Olenellid trilobites, and this leads to

the interesting idea that perhaps the two shared some kind of

symbiotic, mutually beneficial relationship, perishing in tandem

when their required conditions for life vanished. Exactly why

the archeocyathid died out is a major paleontological mystery,

much like the more notorious debate over the demise of the dinosaur.

At present, the most logical hypothesis is that the archaeocyathid,

possessing a very primitive silt filtering system, was unable

to adapt to increasingly muddy waters, that corals and siliceous

sponges were much more efficient, successful adapters in general,

and therefore were primed and ready to claim each available paleo-ecological

niche the archaeocyathid was forced to surrender. This idea finds

support in the lithology of the rocks in which fossil archaeocyathids

are today preserved: They occur almost exclusively in pure limestones

that are uncontaminated by silts or muds.

Because archaeocyathids gained worldwide distribution within

such a finite, "short" life span--around 18 million

years--they are an excellent guide fossil to the early Cambrian

geologic age. Find an archaeocyathid anywhere on the planet and

you know immediately that you are dealing with rocks dating from

the early Cambrian. Their remains have been identified from several

geographic localities, including Morocco, Sardinia, Mexico, Yukon

Territory, British Columbia, Labrador, China, Ural Mountains

of the former Soviet Union, Siberia, East Antarctica, West Antarctica,

Australia, and the United States.

In the United States, archaeocyathids occur in Alaska,

Washington state, Alabama, Georgia, Virginia, New Jersey, Pennsylvania,

New York, Nevada, and California. As a matter of fact, some of

the best archaeocyathid localities in the world occur in western

to central Nevada and eastern California. Here, sprawling across

an area encompassing hundreds of square miles in Inyo County,

California, and neighboring Esmeralda County, Nevada, lies the

land of the archaeocyathid. Most occur in a geologic rock unit

called the Poleta Formation, lower Cambrian in age of course,

a formation named for its extensive and typical exposures in

Poleta Canyon a few miles east of Bishop, California. This is

a remarkably widespread and distinctive series of strata consisting

of alternating limestones, quartzites (heat and pressure-altered

sandstone), and shales. And, in keeping with their invariable

characteristic distribution in other parts of the world, archaeocyathids

occur only in the silt-free limestones. Within the Poleta Formation,

these fossil-bearing calcium carbonate accumulations can be found

in the lowest, or oldest stratigraphic sections of exposures,

below thick deposits of Poleta greenish shales and brownish quartzites

which, while barren of archaeocyathids, are noted for locally

common Olenellid trilobites, annelid trails, and echinoderms.

These preserved archaeocyathids represent, in fact, some

of the oldest recognizable remains of animals with hard parts

from the Cambrian Explosion period, which began 535 million years

ago--a moment in geologic time some 965 million years after the

appearance of what scientific investigators now consider the

first undisputed eukaryote (a cell with a nucleus; all complex,

modern plant and animal life is eukaryotic) and only about 65

million years following the first multicellular eukaryotic animals

at roughly 600 million years ago (the earth is approximately

4.55 billion years old).

Prime hunting grounds for the fossil include western to

central Nevada and the northernmost quarter to third of Inyo

County, California. And one of the very best regions in which

to paleo-prospect for archaeocyathids lies a few miles east of

Big Pine, California, in the White-Inyo Mountains, along Westgard

Pass. The drive over State Route 168 toward Westgard Pass slices

through several thick outcroppings of the fossiliferous limestones

lowest in the Poleta Formation, within which occur locally common

to abundant remains of archaeocyathids, some in primitive reef

form.

To reach an excellent fossil-bearing area where nice specimens

of archaeocyathids can be found, first travel to Big Pine, California,

a wonderful community in the Owens Valley at the base of the

great Sierra Nevada, 15 miles south of Bishop, or 44 miles north

of Lone Pine along Highway 395. From the northern outskirts of

Big Pine along Highway 395, take State Route 168 east. But be

sure to take time to observe the striking specimen of giant sequoia

(Big Tree-Sierra Redwood) at the intersection of 395 and State

Route 168--it's The Roosevelt Tree, planted July 23, 1913 in

honor of US president Teddy Roosevelt, to commemorate the opening

of SR 168 to automobile traffic over Westgard Pass. Proceed two

and four-tenths miles to the intersection with the Death Valley-Saline

Valley Road. Recheck your mileage here, then continue onward

along SR 168.

From the junction with Death Valley-Saline Valley Road,

travel another nine and nine-tenths miles. At this point route

168 begins to cut through a "narrows" in the limestones

of the lower Cambrian Poleta Formation; the limestones here are

massive (showing indistinct layering characteristics), blue-gray

to orange-mottled, and fossiliferous with the remains of archaeocyathids.

For the next six-tenths of a mile the Poleta limestones are prominent

and easily accessible on both sides of SR 168. Find a convenient--and

safe--pullout on which to park (the road does indeed narrow considerably

here; extreme caution must be exercised), then hike to the slopes

above the road to the locally fossiliferous calcium carbonate

accumulations.

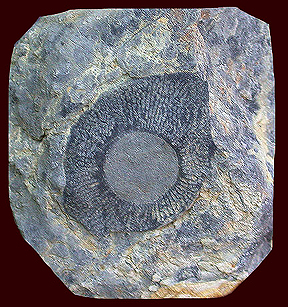

You will need to hike with assiduous attention in order

to observe the best-preserved specimens. Remember, obviously,

that lots of folks have been here before you, including innumerable

geology classes from all over the United States, Canada, and

Mexico--in addition to any number of interested amateur paleontology

enthusiasts and visiting professional paleontologists from all

over the world, as well. And so it is inevitable, then, that

everybody must indeed have their own turn at exploring these

remarkable Poleta archaeocyathid-bearing exposures, and multitudes

who've previously secured a special use permit from the US National

Forest Service invariably collect "a few" sample specimens

to take home. Nevertheless, with attentive, dedicated searchings,

one should be able to spot here many nicely preserved archaeocyathids,

some preserved in their original growth positions for roughly

520 million years in isolated reefy communities. Watch for their

distinctive cross-sections approximately a quarter to one-half

inch in diameter, an oval to circular section revealing a double

outer wall separated by many partitions. In longitudinal, or

lengthwise section, most specimens measure around one-half to

two inches long. Among the more commonly observed genera in the

rocks are Ethmophylum, Ajacicyathus, Archaeocyathus,

Protophaetra, Annulofungia, and Robustocyathus.

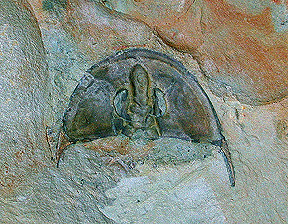

Lying in stratigraphic position above the archaeocyathid-bearing

limestones are exposures of greenish to olive-gray shales and

quartzites representing progressively younger deposits of the

Poleta Formation. In these mostly detrital strata occur scattered

and localized concentrations of Olenellid trilobites, including

such genera as Esmeraldina, Fremontia, Laudonia,

Nevadella, Nevadia, and Holmia. Also identified

from the interstratified shales and quartzites have been brachiopods,

hyolithids (an extinct variety of mollusk), and two rare, early

forms of echinoderms, Helicoplacus and an edrioasteroid--the

oldest remains of echinoderms ever discovered. As a matter of

fact, both Helioplacus and the Olenellids represent the

very first shell-bearing members of their respective phyla (Echinodermata

and Arthropoda) to appear in rocks deposited during the Cambrian

Explosion, and became the first types from their major zoological

groups to go extinct. But the most commonly seen paleontologic

specimens in the Poleta Formation shales and quartzites are very

conspicuous ichnofossils--undescribed annelid and arthropod trails

preserved as sinewy ridges several inches in length, winding

their way across the bedding planes. Over in neighboring Esmeralda

County, Nevada, by the way, the Poleta Formation Cambrian Explosion

sedimentary rocks also yield quality specimens of Anomalocaris,

an extinct, presumably predatory arthropod that probably terrorized

trilobites during the early Cambrian.

While this general area provides excellent opportunities

to find archaeocyathids, other sites along SR 168 between "the

narrows" and Westgard Pass up ahead (farther north) also

often disclose locally common examples of additional early Cambrian

invertebrate fossils preserved in the Poleta Formation and the

stratigraphically older underlying Montenegro Member of the Campito

Formation--a predominantly detrital unit of greenish to tan shales

and brownish quartzites that yield sporadic occurrences of Olenellid

trilobites, primarily. Outcropping below the Montenegro Member

is the Andrews Mountain Member of the Campito Formation; and

near the top (youngest horizons) of the Andrews Mountain Member,

in strata close to 522 million years ancient, the oldest trilobites

in North America--and possibly the world--have been discovered,

an Olenellid form resembling the Siberian trilobite Repinaella.

For those planning a visit to the Westgard Pass area in

search of paleontologic specimens, several fine reference publications

are available for study. Among the more informative works are:

Guidebook for Field Trip to Pre-Cambrian-Cambrian Succession

White-Inyo Mountains, California by C.A. Nelson and J. Wyatt

Durham; "Stratigraphic Distribution of Archaeocyathids in

the Silver Peak Range and White and Inyo Mountains, Western Nevada

and Eastern California" by Edwin H. McKee and Roland A.

Gangloff, Journal of Paleontology, volume 43, number 3,

May, 1969; and Geologic Map of the Blanco Mountain Quadrangle,

Inyo and Mono Counties, California, U.S. Geological Survey

Quadrangle Map 529. This last one shows the geographic distribution

of outcrops of rock formations in the Westgard Pass area, drawn

over a topographic base map--an invaluable reference to consult

when exploring here.

In addition to the significant fossils, there are other

wonders to explore in the Westgard Pass lands. To the immediate

west and north, for example, lie the famous Bristlecone Pine

groves in the White Mountains at elevations over 10,000 feet.

Here, the oldest continuously living, non-cloning thing on earth--the

Bristlecone Pine, a few have been accurately calculated at over

4,000 years old--survives atop a geologic rock formation, the

Reed Dolomite, that dates from earth's oldest geological division,

the Precambrian of over 550 million years ago. This is certainly

a unique and appropriate coincidence.

An aside here. Another ultra-significant Precambrian-Cambrian

transitional stratigraphic section can be studied in the Alexander

Hills District, southeast of Death Valley National Park,

a California Mojave Desert locality that produces: Precambrian

stromatolites over a billion years old; early skeletonized eukaryotic

cells of testate amoebae around three-quarters of a billion years

old; and early Cambrian trilobites, archaeocyathids, annelid

trails, arthropod tracks, and echinoderm material.

When hunting for fossils in the Westgard Pass region, be

sure to abide by the rules and regulations--don't keep anything

found within the Inyo National Forest unless you've obtained

a special use permit from the US Forest Service ranger station

in Bishop, California. Also, by way of caution, elevations here

range from around 7,000 feet to way over 10,000 feet, so try

to keep your physical activities moderate until you are well-acclimated.

There is a vast area of potential fossil-bearing material to

explore and it would be inadvisable--not to mention downright

risky--to try to cover it all in a single day. With so much recreation

so accessible, this would be an ideal place for a stay of a week

or two, preferably during summer when the roads at higher elevations

are open.

During the early Cambrian, the Westgard Pass area was a

warm, shallow sea situated near the equator in which numerous

species of now long-extinct animals flourished--among them, the

very first shell-bearing examples of three great zoological categories

to appear in sedimentary strata deposited during the crucial

Cambrian Explosion period of 535 to 510 million years ago--Olenellid

trilobites, Helicoplacus echinoderms, and archaeocyathids

who, individually, belong to the living phyla Arthropoda, Echinodermata,

and Porifera, respectively.

Perhaps we may never fully understand the exact reasons

for their complete disappearance, yet because Olenellid trilobites,

Helicoplacus echinoderms, and archaeocyathids were the

first of their respective phyla to contribute no more to the

geologic record beyond the early Cambrian 510 million years ago,

their paleontological presence together at Westgard Pass demonstrates

that they never really went away; they're still alive, on their

way to a kind of immortality--a vanished invertebrate association

of Cambrian Explosion creatures who now survive not only in the

rocks, preserved in place for over a half billion years, but

also in the lives of prehistory explorers, so that we may learn

of a time and remember for all time a distant age when multicellular

animal life on earth was relatively new, and of perilous existence.

|